Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. If you’re part of a few extremely specific Twitter/Bluesky/Mastodon/mailing list circles, you may have come across tech venture capitalist Marc Andreessen’s1 latest screed, “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” It’s a strange, interesting, and at times (unintentionally) hilarious 5000-word document, and even if you’re not in one of the many groups he offends in the piece,2 I’m going to argue that you should care about this manifesto—and manifestos in general—not for their content per se, but for what’s behind them and what we can learn from them, especially when that’s not what their authors want us to learn from them.

There’s an inherent grandiosity to a manifesto. They’re declarations, “gigantic speech acts” meant to lay out a position and, maybe, provoke a response. Tech has a long history of them. Some of the earliest include the 1985 GNU Manifesto promoting the Free Software movement to the 1986 Hacker’s Manifesto defending computer exploration to the 1993 A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto promoting privacy through encryption—tech has been rather fond of its big declarations for decades.

Manifestos tend to be a response to a certain moment, and one of the reasons why the early years of the Internet had so many of them was because cyberculture was in flux. Computing technology was still developing, and there were big fights over aspects of how it should progress. Some were more narrow, like the GNU Manifesto, but others were broader. One of the most well-known is A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, penned by John Perry Barlow in 1996. It was written in direct response to the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (which included the Communications Decency Act that cyber-libertarians of the time deplored). It’s interesting on a number of levels, so we’ll look at it alongside the Techno-Optimist Manifesto.

I think there are three ways of understanding a manifesto. The first, basic level, is as a genuine mission statement. The second is as an ego trip, and the third is as a commentary from a particular group about the culture of the time. Let’s look at each in turn.

The Mission Statement

The manifesto as a mission statement is the foundational level of understanding a manifesto. Of course it’s trying to promote an idea. Usually, that idea is right up in the title. This is also the level that allows for criticism of the ideas expressed in the document.

When he wrote A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace in 1996, Barlow was trying to assert cyberspace’s autonomy from government and corporate control, painting it as a borderless, disembodied, liberated utopia. If you think that sounds like an exaggeration, read the first few sentences:

“Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

It was a rejection of government authority over the Internet, arguing that they had not “solicited nor received” the consent of the governed and that governments attempting to assert control over cyberspace were thus illegitimate and doomed to fail.

The Techno-Optimist Manifesto seems to be a response to recent advances in AI and corresponding critiques of its impacts. Opening lines:

“We are being lied to.

We are told that technology takes our jobs, reduces our wages, increases inequality, threatens our health, ruins the environment, degrades our society, corrupts our children, impairs our humanity, threatens our future, and is ever on the verge of ruining everything.”

It argues that we have a moral obligation to advance technology, especially AI, as quickly as possible to create a society of unlimited abundance, and that anything other than an unwavering faith that technology is universally good and situating it in a market economy is the only thing that can improve the world is bad:

“We believe any deceleration of AI will cost lives. Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.”

You can easily criticize both of these on their merits (or lack thereof). What Barlow’s Declaration ignores is that terrible things happen on the Internet when you only rely on “unwritten codes” and cross your fingers that everyone follows the Golden Rule, “the only law that all our constituent cultures would generally recognize” (that’s how you end up with cesspits like 4chan). Even at the time, women and people of color were being harassed online, countering his assertion that “We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth.”

Andreessen’s manifesto is a fundamental mischaracterization of the non-techno-optimist perspective. Note that I didn’t call it “techno-pessimist”—I don’t consider myself a “techno-pessimist,” even though I am supporter of several of the “enemy” ideas he lists. I love technology (or else I wouldn’t study and use it all day), but I am skeptical of it and its effects. (And I would think that Andreessen would be supportive of skepticism considering how much he extols the scientific method.) He’s characterizing anyone who doesn’t subscribe to his brand of techno-optimism as an enemy/Luddite/Communist3 fundamentally opposed to progress—which is morally condemnable according to the last quote—but people who support tech ethics and risk management aren’t reflexively opposed to progress. In general, we just don’t agree with the statement that:

“…technology is universalist. Technology doesn’t care about your ethnicity, race, religion, national origin, gender, sexuality, political views, height, weight, hair or lack thereof. Technology is built by a virtual United Nations of talent from all over the world. Anyone with a positive attitude and a cheap laptop can contribute. Technology is the ultimate open society.”

Technology is not universalist because we are not universalist, and technology is created by us. Technology does care about your ethnicity if it’s used in an ethnicity-profiling system, your race if AI is trained on a biased dataset, your national origin if you live somewhere with limited access to the Internet, your gender if you’re a girl being told that computer science is for boys. I could go on, but we have to get to the second way of understanding a manifesto.

The Ego Trip

As I noted before, a manifesto is speech on a grand and massive scale. You’re writing authoritatively for a wide audience. Whether or not the movement has delegated you to, you’re writing on behalf of one. That’s why there’s an irony to Barlow asserting that governments lack the consent of the denizens of cyberspace. He also lacked their consent to write on their behalf rejecting tech regulation, which people are generally in favor of. His views were shared by some, but not the majority. A manifesto can take the views of a vocal minority and expand them to seem even bigger than they are.

Andreessen takes this to the extreme, writing on behalf of a very small group and trying to argue that he’s fighting on behalf of all of humanity, but his argument is inextricable from his identity as a very rich man who made his wealth from investing in technology companies. In pointing out some of its more tone-deaf aspects, Wired argues that it would be better if called “The Techno-Billionaire Manifesto,” and TechCrunch asked, “When was the last time Marc Andreessen talked to a poor person?” My favorite example is when he attacks the UN Sustainable Development Goals as enemies “against technology and against life”; the goals include eliminating poverty and hunger and promoting gender equality. Again, it takes a certain hubris to be able to argue “that regulation and accountability are bad” but to make it sound like it’s for the benefit of all of us.

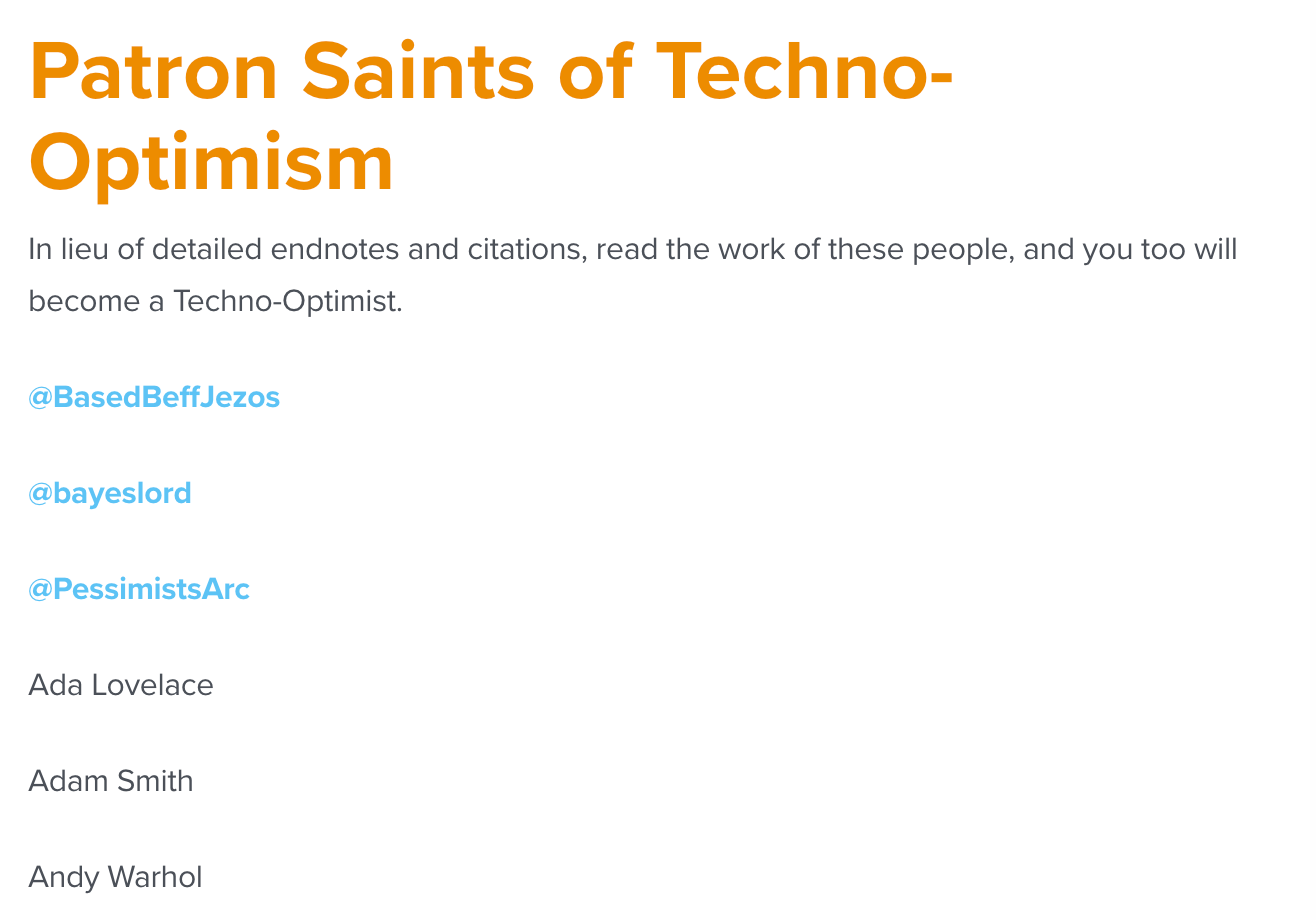

According to my cursory research, the manifesto seems to be a format typical of men. Manifestos by women tend to subvert the masculine form by using them for feminist declarations.4 And while I won’t presume to forward a reason, Andreessen’s piece comes across as hyper-masculine in lines like “We believe in ambition, aggression, persistence, relentlessness – strength.” You can also argue that this is what you need to publish a manifesto,5 the qualities that undergird the confidence to write a whole bunch of sweeping “we” statements (or to assert that a Twitter account called “BasedBeffJeszos” is a “patron saint” of your movement). But perhaps my “ressentiment”6 is showing. Let’s turn to the broader context.

The Two-Sided Cultural Commentary

I don’t think Andreessen actually believes everything he’s writing; that’s not the point of a manifesto. The point of a manifesto is to promote a narrative that would be convenient for the author if believed.7 A professor teaching about manifestos describes them as vehicles for “bullshit” (used in the technical sense of speech where the speaker doesn’t care about its relationship with the truth). In the sense that manifestos promote an unproblematic vision of a certain idea, they’re essentially promoting a utopia, and if you’re trying to get people to believe in your utopia, you need bullshit because utopias never come true.

Barlow’s Declaration told us how a certain group of mostly white, mostly male techies felt about cyberspace—that it was a place of radical equality, despite the fact that it was most welcoming to the early adopters who were unable or unwilling to see the barriers keeping others from accessing and having the same experience in cyberspace. If this had been true, it would have been nice for them, because they wouldn’t have had to confront the thorny issues of inequalities that cyberspace illuminated. It also would’ve been convenient because many of them worked in tech, and less regulation would certainly have made their lives easier. However, his call to action was mostly ignored; the Internet is subject to the laws of governments in the physical world, and we probably have that to thank for it being a (somewhat) civilized place.

What we can learn from Andreessen’s piece is that Marc Andreessen is certainly annoyed, and possibly scared. His fortune is founded on investments in technological advancements, and anything that slows technology also threatens his business. Kevin Roose and Casey Newton of Hard Fork noted that Andreessen has to flatter founders and investors so that they’ll work with him, and promoting a culture of unabashed acceptance of technology helps in that mission; criticism takes direct aim at his work and makes it harder. Perhaps his vision is so distorted by his position that he does genuinely believe it’s correct, but his experience is not the norm. Although he claims that the techno-optimists believe in “undertaking the Hero’s Journey, rebelling against the status quo, mapping uncharted territory, conquering dragons, and bringing home the spoils for our community,” the thousands of unhoused people in San Francisco might ask where those spoils are really going. (The heroes in the myths always seemed to keep the treasure for themselves, too.)

Manifestos are not just revealing about the movement they promote, but about the force that provoked them. Barlow’s Declaration showed that the prospect of regulation made a certain class of Internet denizens very unhappy. The fact that it’s still referred to and occasionally revived shows that some still yearn for the mirage of a disembodied, egalitarian Internet, which is becoming more and more relevant with the revival of VR. Andreessen’s manifesto shows us that the “techlash” is working. If they have to construct straw men to try and burn you, you’re doing something right.

Next time you come across a manifesto, remember to not buy what it’s selling at face value, but to consider it as a marketing tool and interrogate it as skeptically as you would any traveling salesman. I won’t presume to speak on behalf of everyone who objected to parts of Andreessen’s manifesto, but I want to reclaim the term “techno-optimist.” I am optimistic about what technology can do for humanity, but I’m not a starry-eyed, libertarian Pollyanna. True optimism is not foolhardy, Panglossian acceptance. It is hope, nurtured by a faith in an ultimately good outcome, but tempered by the knowledge that it might not work out.

The closest I will get to a rallying cry is this: let us reclaim the torch of techno-optimism.

Marc Andreessen, who helped create one of the original web browsers, is now a tech venture capitalist with an estimated net worth of $1.53 billion largely derived from the tech industry. He also has a habit of posting this sort of text.

At one point, he lists the “enemy” ideas of techno-optimism engaged in a “mass demoralization campaign… against technology and against life.” They include: “existential risk”, “sustainability”, “ESG”, “Sustainable Development Goals”, “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management”, “de-growth”, “the limits of growth”. Many of these, apparently, are “derived from Communism.” Even people who support his argument think this part is a bit iffy.

He uses all three of these terms, and as far as I know, Communism doesn’t have anything to say about holding back technological progress (or, for that matter, about ESG and the Sustainable Development Goals, see footnote 2). There’s also an argument that he’s misunderstanding the Luddites, whose original mission was not anti-technology but pro-worker’s rights.

For tech-related examples, see Donna Haraway’s 1985 A Cyborg Manifesto or The Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century from 1991. For non-tech examples, see Olympe de Gouges’s 1791 The Declaration of the Rights of Women, The Combahee River Collective Statement from 1977, or the maybe-satirical 1967 SCUM Manifesto by Valerie Solanas, best known for shooting Andy Warhol.

Some might also argue that they’re what you need to publish a Substack, but that’s beside the point (thanks, Mike).

Apparently “a witches’ brew of resentment, bitterness, and rage that is causing them to hold mistaken values, values that are damaging to both themselves and the people they care about.” It’s almost Halloween, but I don’t recall drinking any witches’ brews recently.

Note that “if believed” and “if true” are two separate things.

Thumbnail generated by ChatGPT interfacing with DALL-E 3 through the generated prompt “Illustration capturing the essence of 'male ego' using a mix of geometric and organic forms in muted tones.” I almost went with the hilarious “Purely abstract composition of geometric shapes, lines, and splashes in a harmonious dance, representing the complexity of the male psyche.”