ER 21: On Chaos Demons (aka AI Companies)

Or, what fights over OpenAI and the AI Act tell us about the industry

Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. After a Thanksgiving break, we’re back to our regularly scheduled programming, so there will be a Weekly Reckoning this week. But quite a lot has happened since we last caught up, and I thought a longer piece was in order to help us think through what’s going on in the AI world, which is in chaos, but not just because of OpenAI. Big AI companies are causing mayhem on both sides of the Atlantic, threatening AI regulation but also maybe revealing that the emperor has no clothes, so to speak.

Many tech writers lost a good chunk of their Thanksgiving vacations last week when, Friday around noon, the OpenAI board announced that they were removing the OpenAI CEO, Sam Altman, effective immediately. The rumor mill swung into full gear, and depending on who you asked, the move was either:

A response to Sam Altman lying to the board (the board’s official message).

A clumsy coup by effective altruists1 aimed at taking control of the company.

A counterattack precipitated by fears that OpenAI had achieved AGI and would deploy it irresponsibly.

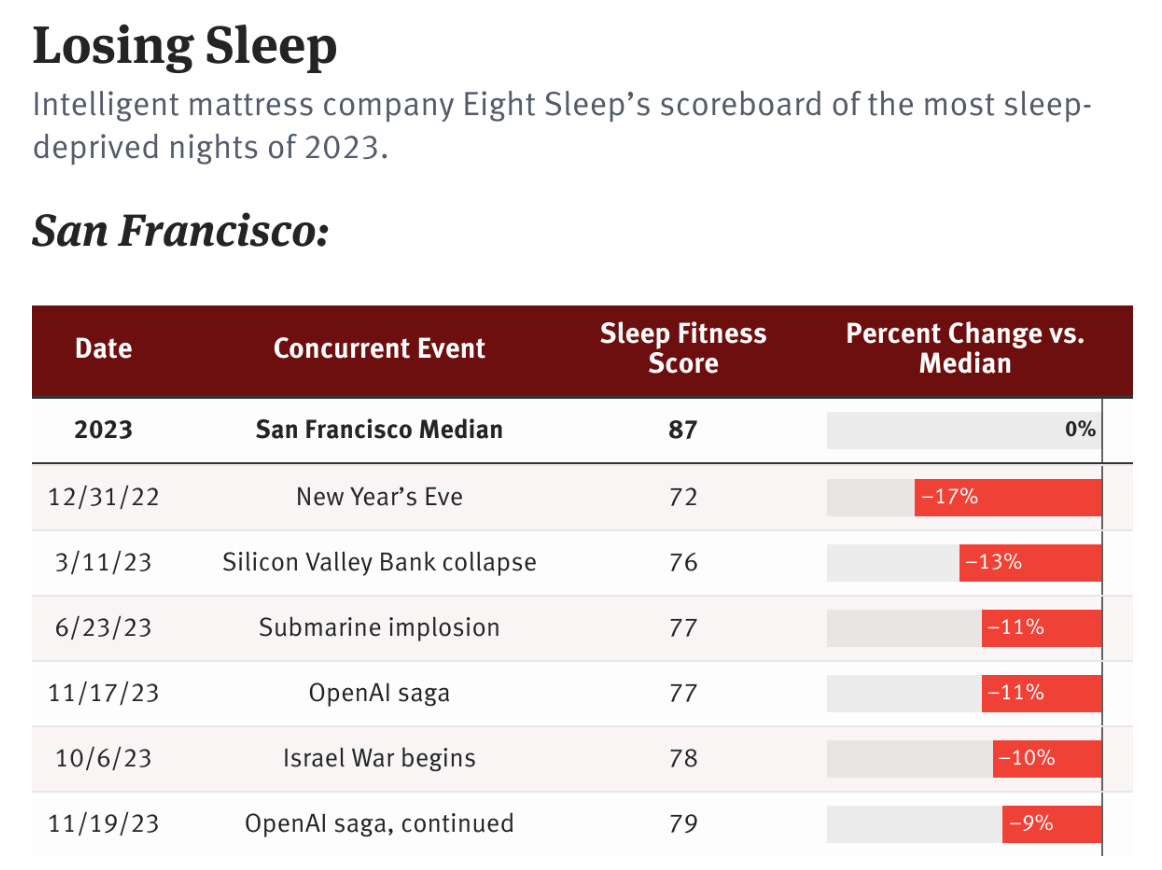

Five days, two interim CEOs, 700 signatures on an OpenAI staff letter2 demanding Sam’s return and the board’s ouster, 700 corresponding job offers from Microsoft (who at one point announced Altman would lead a new AI unit within the company), one apology from a board ringleader, and three board resignations later, Sam Altman was back at OpenAI, with a new board, a measurable net loss of sleep in San Francisco, and a lot of generated confusion.

Based on what I’ve managed to piece together (a good recap is here), my interpretation of the situation hews closely to #4. The board seemed to be genuinely concerned that Sam Altman was pushing OpenAI to commercialize its models too fast and not communicating with them about his actions, which the board felt was a safety risk. In accordance with the charter, they took actions to remove him, but, according to one former senior corporate executive who spoke to me on background, were “a bunch of academics and techies with no public relations experience and no business management sensibility” and bungled it horribly. As a result, the people who were supposed to be a bulwark between OpenAI and the rest of the world are out, and Sam is back in, seemingly more powerful and impervious than before. However, OpenAI still has a lot of questions to answer, including exactly what went down between the board and Altman, and how they’ll prevent it from happening again.

A lot of Europeans have been losing sleep as well because the landmark EU AI Act is in jeopardy. It’s been under development since 2021 and is finally in the last phase of negotiations, the “trilogues,” where the European Parliament, Commission, and Council all get together and hammer out final details. Things seemed to be going well up until two weeks ago, when France, Germany, and Italy—the EU “big three”—suddenly issued a statement trying to water down how the AI Act would regulate foundation models (which underlay generative AI tools like ChatGPT). It had already been a big scramble to add foundation models into the AI Act when ChatGPT was released, and the European Parliament saw removing them as a non-starter and even a “declaration of war.” The “big three” claim that their approach, which would involve “mandatory self-regulation” (which, without any proposed sanctions, is not a thing) would be more in line with the risk- and application-based approach of the AI Act, but detractors say that it would render the AI Act toothless against the models that need to be regulated most, on top of putting the entire AI Act at risk.

This wasn’t a sudden change of heart from the “big three”—especially not France, which had been one of the main forces lobbying to include foundation models in the AI Act—but rather the result of concerted lobbying from European AI companies, including France’s Mistral and Germany’s Aleph. Lobbying from AI companies isn’t new; OpenAI has done a fair bit of lobbying itself. But this is the first time in the AI Act negotiations that it’s seemed like governments are directly doing the bidding of their country’s national champions. Honestly, it’s likely a response to the massive success of OpenAI. European companies are afraid of falling behind, and their governments are afraid of the ramifications for their national AI/tech industries. If this continues, we risk regulatory capture by Big Tech where they essentially make the rules that govern them—or potentially kill the AI Act altogether.

Although these two cases seem very different, they both show the power of AI companies. They have a stranglehold not only on lobbying, but also on our cultural imagination. When ChatGPT first launched, it consumed the Internet (or at least specific corners of it) for days. Now, it’s one of the fastest-growing start-ups ever, and that plus a juicy Succession-style leadership drama had us all on the edge of our seats (even my relatives who don’t care about AI were talking about it over Thanksgiving). But these are also symptoms that all is not well in the AI industry. Quite frankly, there’s not enough competition. AI is a technology that tends towards monopoly in development—because of the immense computational resources required to develop large models—and democracy in deployment, because once a model is developed, it’s trivially easy to share and run (barring red tape imposed by governments/companies). But this means that a small handful of companies have huge sway because of their economic power. We need not just companies like Meta and Anthropic and Mistral and Aleph to compete with OpenAI, but smaller start-ups and even models from academia and civil society.3

This sounds like a pipe dream, but US regulators are anticipating this. The National AI Research Resource would help make AI development more accessible by providing compute power and datasets to underserved researchers at higher education and nonprofit institutions. Funding this and creating more initiatives like it in the EU and elsewhere would help spur the innovation necessary to bring more players into the game that’s currently being defined by a very few individuals. But first, we need to resist the regulatory capture that threatens effective regulation. The promise of more measures to boost innovation could bolster this, as if countries are reassured that they will be able to nurture more AI companies, they may back down from protectionist actions designed to benefit only their existing players. China is a good example of how regulation and innovation are not mutually exclusive: despite passing several laws regulating the AI sector, over 130 LLMs are available in China, and they’re narrowing the performance gap to models like GPT-4 and Claude.

As for our cultural fascination with Big Tech, well, that’s not going away anytime soon. They are still creating huge, impactful technologies, and deserve to be subject to scrutiny, even when (and especially when) behind-the-scenes drama bursts on to the main stage. In a way, this helps us remember that the leaders of our Big Tech companies aren’t deities,4 but mere mortals who can do cool things and screw up doing them just like the rest of us.

Effective altruism is centered around the idea of doing the most good with the money you have, which sounds fine on its face, but very quickly gets very problematic.

The company only has 770 employees.

The US government and Intel are backing a trillion-parameter model called ScienceGPT, which is being trained by researchers at the Argonne National Lab, but details on its purpose are scarce except that it’s to “speed up research.”

Or if they are, it’s in the Greek/Roman sense where they have flaws and conflicts and clashes (no word on if Altman has ever turned into a swan).

Thumbnail generated by DALL-E 3 via ChatGPT with the generated prompt "An abstract impressionist painting depicting the concept of 'technological chaos demons' with a cool color palette. The artwork should feature a blend of technological elements, such as wires, circuits, and digital interfaces, intermingled with abstract shapes and forms that suggest demonic figures. The color palette should be dominated by cool tones, including shades of blue, green, and purple, to create a harmonious yet chaotic atmosphere. The style should capture the essence of abstract expressionism, emphasizing emotional depth and spontaneous brushwork."