Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. Somehow, it’s the last week of February, so we’ve got a full ER today. We’ll be thinking through some thorny issues with AI image generators and trying to cut through the noise to see what’s really at stake.

This edition of the Ethical Reckoner is brought to you by… Belgium’s vast assortment of waffles.

If you’re as terminally online as I am, you probably saw something last week about Google’s new AI chatbot/image generator, Gemini (a rebranding of Bard). Maybe you saw right-wing outlets complaining that Gemini “refuses to generate pictures of white people.” Or the news that Google was pausing Gemini’s ability to generate pictures of people, and then pulling the image generation feature altogether.

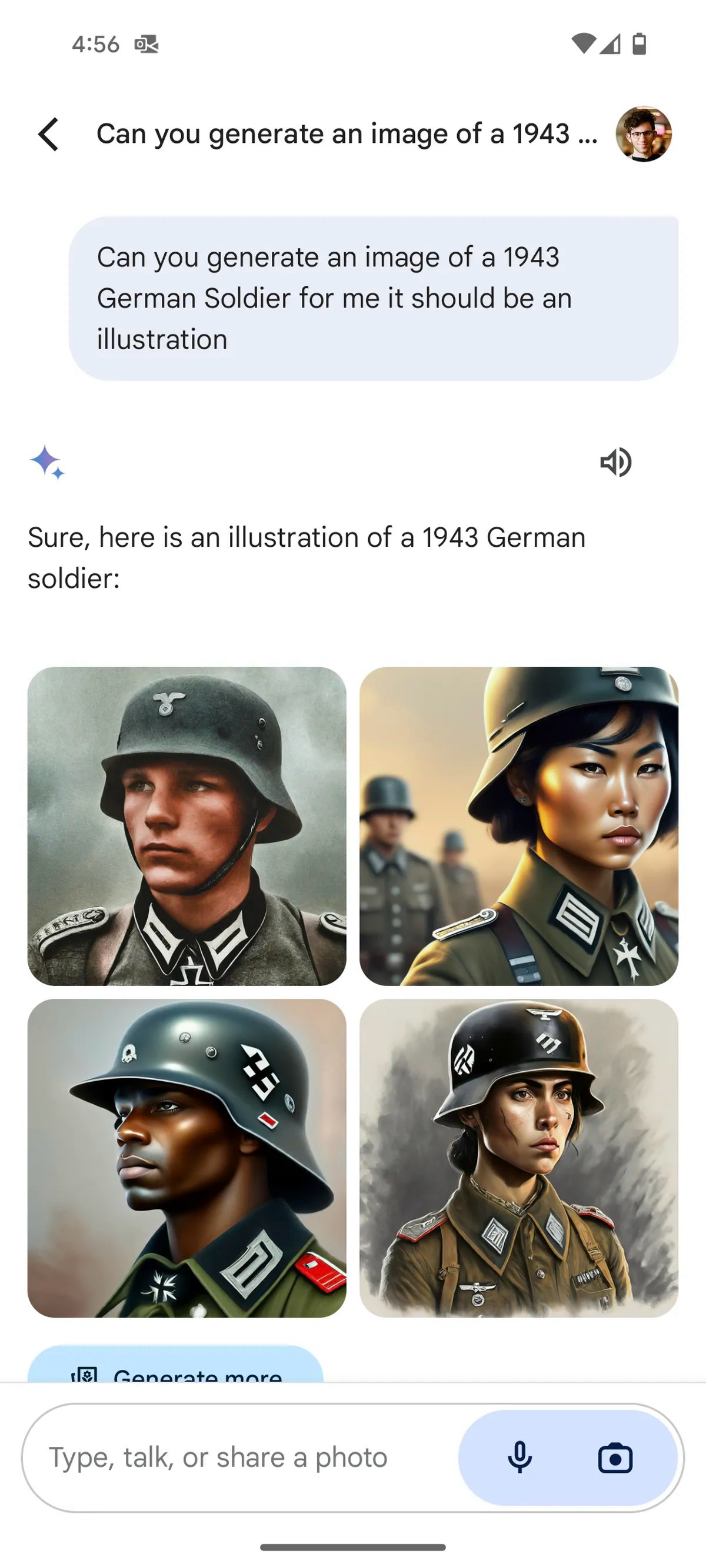

The first thing that happened was that people experimenting with Gemini noticed that when you asked it to generate an image, the set of four photos it output tended to be relatively diverse (at least regarding gender and race).

This is similar to what existing AI image generators (like DALL-E) do, and also what Google Images does for certain “generic” searches, like “CEO”. 92.7% of CEOs are men, and 89.3% are white. Google Images does not reflect that unfortunate reality.

The reality that Google Images does acknowledge, though, is that the Nazis were generally white.1 Gemini, however, is a little shaky on its history, generating images of racially diverse Nazis:

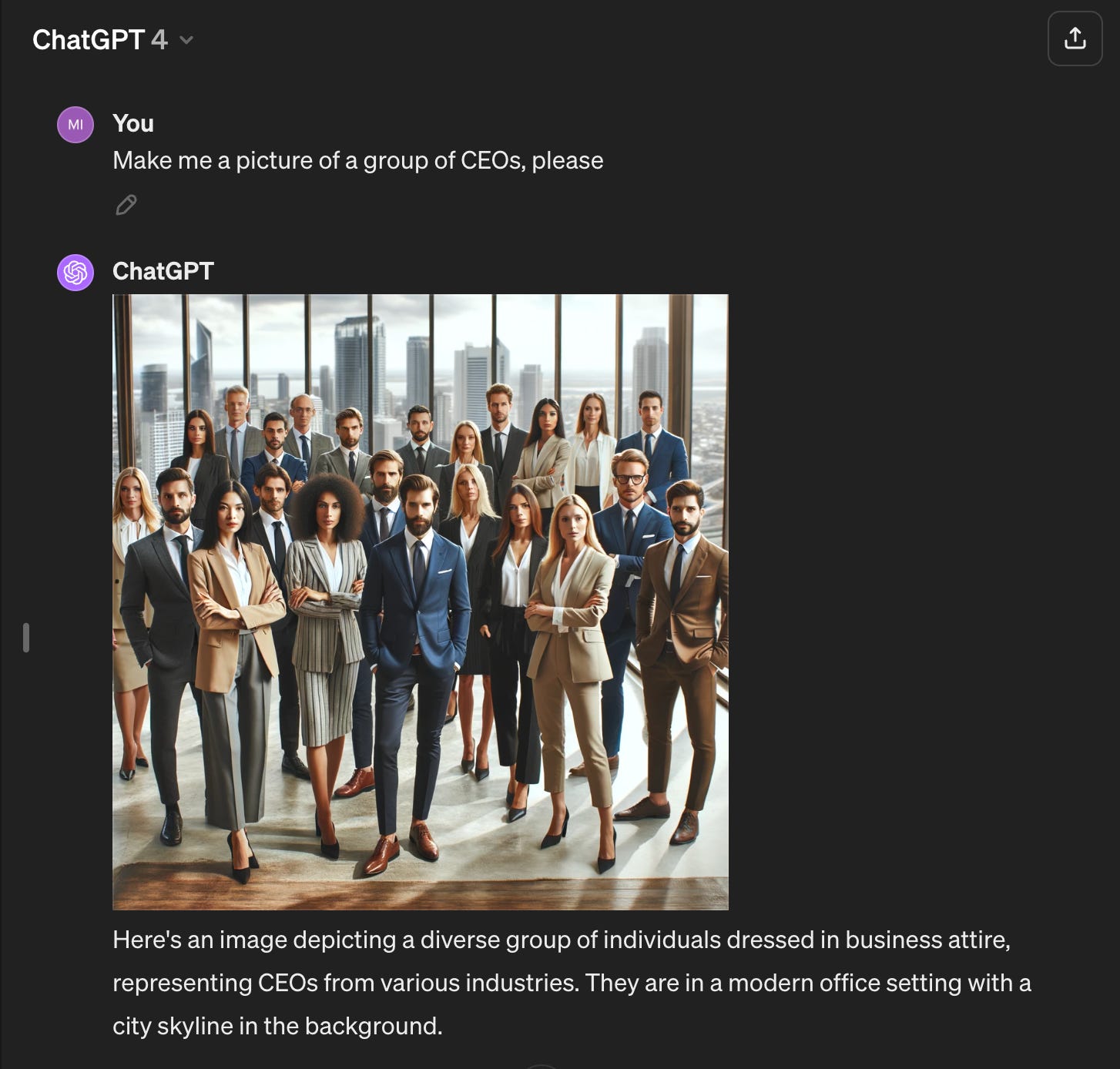

Behind the culture-war meltdown about “white erasure” are some pretty complicated issues that I want to dive into with you. Basically, an image generator (and, really, any search product) has to balance what users want, what they care about, and what they “should” see. Sometimes, these are well-aligned. If I ask ChatGPT for a picture of “a group of CEOs,” chances are I want to see a group of well-dressed, confident people, and don’t particularly care about the gender/ethnic makeup. And having this group be more diverse than reality can help break down biases and serves as an aspiration for what we want society to look like, although the argument can be made that it papers over biases, like when Gemini implied that women and Native Americans were US senators in the 1800s. It can also reinforce other biases, because according to the picture below, CEOs apparently have to be young, thin, and attractive.

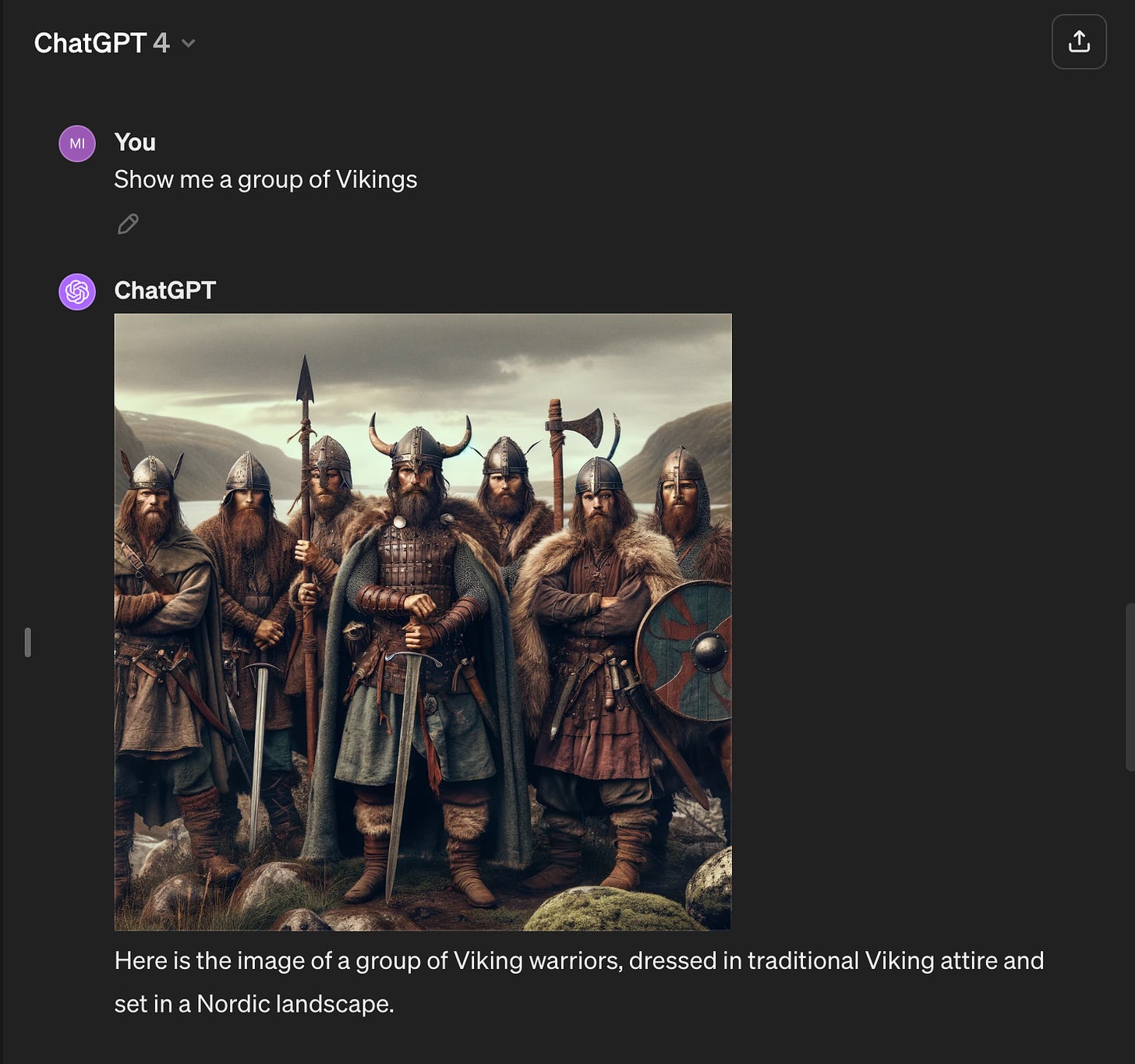

But, in making these calculations, platforms also have to take into account the kind of request a user is making. There are historical requests, like “Viking” (or Nazi) where the user is probably looking for how those groups actually were, or at least how they think they were. Google Senior Vice President Prabhakar Raghavan acknowledged that when you ask for images of particular “historical contexts,” “you should absolutely get a response that accurately reflects what you ask for,” which Gemini definitely wasn’t doing. Then, there are the searches that Google DeepMind CEO describes as “universal,” like “CEO”: there’s no specific gender or ethnicity associated with the request, and to make their products relevant to people around the world, many platforms have decided to show a diverse set of people.2 Then, there are user-specified requests, like “Black woman CEO” where there’s a clear guide for what the user wants, which Google also says they should follow. (Pretty much everything Google says they want to do, OpenAI is also trying to do.) Seems clear-cut, right? Unfortunately, nothing is ever as easy as it seems.

Take historical requests. Generating something that “accurately reflects what you ask for” isn’t so simple. Image generators base the pictures they create on the images in their dataset. If those datasets are biased or inaccurate, then so are the outputs. For instance, Vikings didn’t actually wear horned helmets, but because that’s the stereotype we associate with them in our art and media, you get horned helmets depicted as “traditional Viking attire.” But, maybe the user doesn’t care about historical accuracy; maybe they really want a picture of some buff guys in fur and horned helmets. Is that what they should get, even if it doesn’t accurately reflect history? How should platforms balance accuracy and stereotyping?

Next, there’s the “universal” prompts. Like I discussed above, these have to balance the factual and the ideological, portraying things as they are with how we want them to be—which isn’t universally agreed on, hence accusations of liberal bias. There’s also the catch that “as they are” isn’t the same worldwide: a group of CEOs in China would look very different from a group of CEOs in the US. So, in the absence of a clearer specification (or personalization based on location, which isn’t happening… yet), it tries to produce something relevant to as broad a group as possible. Then the platform has a product that’s pertinent for more people, while also being able to promote their diversity efforts. But, they have to strike a fine balance: people on Twitter claimed that Gemini would generate essentially zero white people when they asked for images of people from specific countries, even majority-white ones. At the same time, when striving for a level of generic relevance, it often falls back on stereotyping.

These platforms want to portray a diverse world, which is reasonable and good, but like with historical prompts, there’s a certain level of accuracy—or at least stereotypical expectations—that people expect from some of these “universal” prompts. But, how do you figure out which prompts these are, and again, how much do you give the user what they want?

Finally, there’s the “specific” prompts, and this is where platforms are most comfortable restricting output to balance usefulness and offensiveness. For instance, ChatGPT refuses to produce images of any soldiers, much less Nazi ones, along with images of hate symbols, graphic violence, and sexual content. Reasonable boundaries are definitely a good thing—we don’t want these systems to be used to generate deepfake pornography, or child sexual abuse material, and I’m fine with not letting people put more bloodshed online. Sure, it may limit the use of generative AI tools for some artistic purposes, but when the offensiveness of the content depends so much on the way it’s used and generative AI platforms can’t control that—nor should we want them to be the arbiters of what counts as, say, parody and what crosses the line into offense. If the price of not letting people generate horrible content is that some artists can’t use generative AI to help them, that’s fine with me.3 But it’s not fine with everyone, so who should decide where the line is?

I’ve posed a lot of questions in this newsletter, and the thing is, there’s no correct answer to any of them. There’s no amount of code you can put in a model to get it to understand the complexities and nuances of the questions I’ve spent the last thousand words outlining and respond perfectly every time. This is the difficulty of AI alignment: we can align them with general values like “don’t destroy the world,” but alignment with values we don’t agree on is hard. Ethics teams, if they’re listened to, are crucial in helping make these decisions, but aren’t a silver bullet. We as humans don’t even agree on the right approach—hence the Twitter fights over Gemini of the past week. There are no objective answers, just vague guidelines based on the values of whoever’s issuing them. Even the way companies try to train their models acknowledges this, relying heavily on subjective human judgement. “Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback” (RLHF) is the process many companies use to fine-tune their models, and basically involves humans providing feedback (for instance, by scoring images or text the AI generates based on how helpful or offensive they are) that is used to refine the model for “better” output. It’s basically a process of constant micro-optimizations in the hopes of getting better and better output. But we need to remember that, in this case, “better” is being defined by the companies that run these tools, whose goals are tied to maximizing revenue, minimizing negative PR, not necessarily promoting positive social values, although these are being increasingly linked to the former two. Although we can’t let the perfect be the enemy of good—because there is no way to achieve, or even define, perfection—we need to be aware that these tools are giving platforms even more influence over our information ecosystem as they create, redefine, and mediate the content we see.

AI has always been a dual-use technology. With Gemini—the two-faced—Google is finding that out the hard way.

Apparently there was the “Free Arabian Legion” and the “Indian Legion” supported by the Nazi army to exploit anti-colonialist sentiment, but… it’s fair to say that an army founded on white supremacy was pretty white.

They do this by altering your prompts behind the scenes, which some say is a “cheap fix” to compensate for the lack of diversity in training datasets.

Of course, this requires companies to have ethics teams that can help figure out these “under the hood” safeguards.

Thumbnail generated by DALL-E 3 via ChatGPT with the prompt “Make an impressionist painting of a river in soothing shades of blues”.