Welcome back to the newsletter! It’s the last Monday of the month, so we’ll be zooming out for an Ethical Reckoner—the newsletter’s namesake and original format. Next week, we’ll be back with a Weekly Reckoning covering all the tech news.

Today, I want to talk about tech adoption, and more specifically how we narrativize it. I recently read famed tech journalist Kara Swisher’s fantastic Burn Book, where she recounts her decades of covering the tech industry, including mobile phones and the dot-com boom. I think that looking at historical tech development, funding, and hype—and how we narrativize it in the moment and after the fact—can tell us a bit about where AI is heading.

This edition of the Ethical Reckoner is brought to you by… terrassenweer (I wish).

We think about a lot of tech adoption as rapid and inevitable, and when you zoom out enough, it often looks like that, but that elides a lot of bumps in the road. Some technologies have genuinely been adopted quickly. Others have had a slow-and-steady adoption, and still more have gone through wild boom-bust cycles.

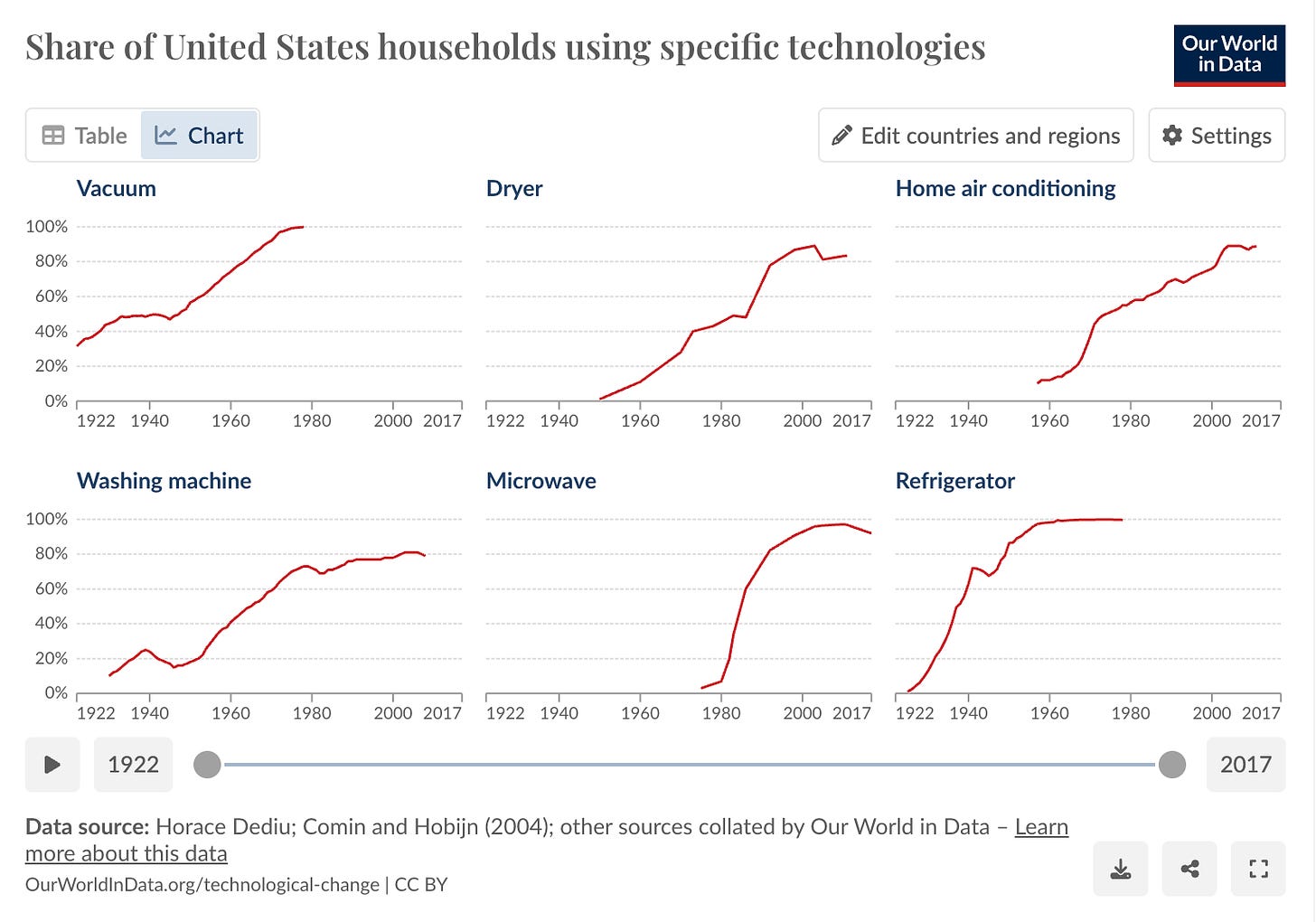

There aren’t many technologies that have been adopted extremely quickly. Let’s look at home appliances in the US.

Most of these were adopted slowly over time (with interesting dips for the washing machine and refrigerator in the 1940s—but even WWII couldn’t stop vacuum adoption). The exception is the microwave, which languished for five years at single-digit adoption rates before exploding in popularity (likely due to some truly fantastic advertising campaigns).

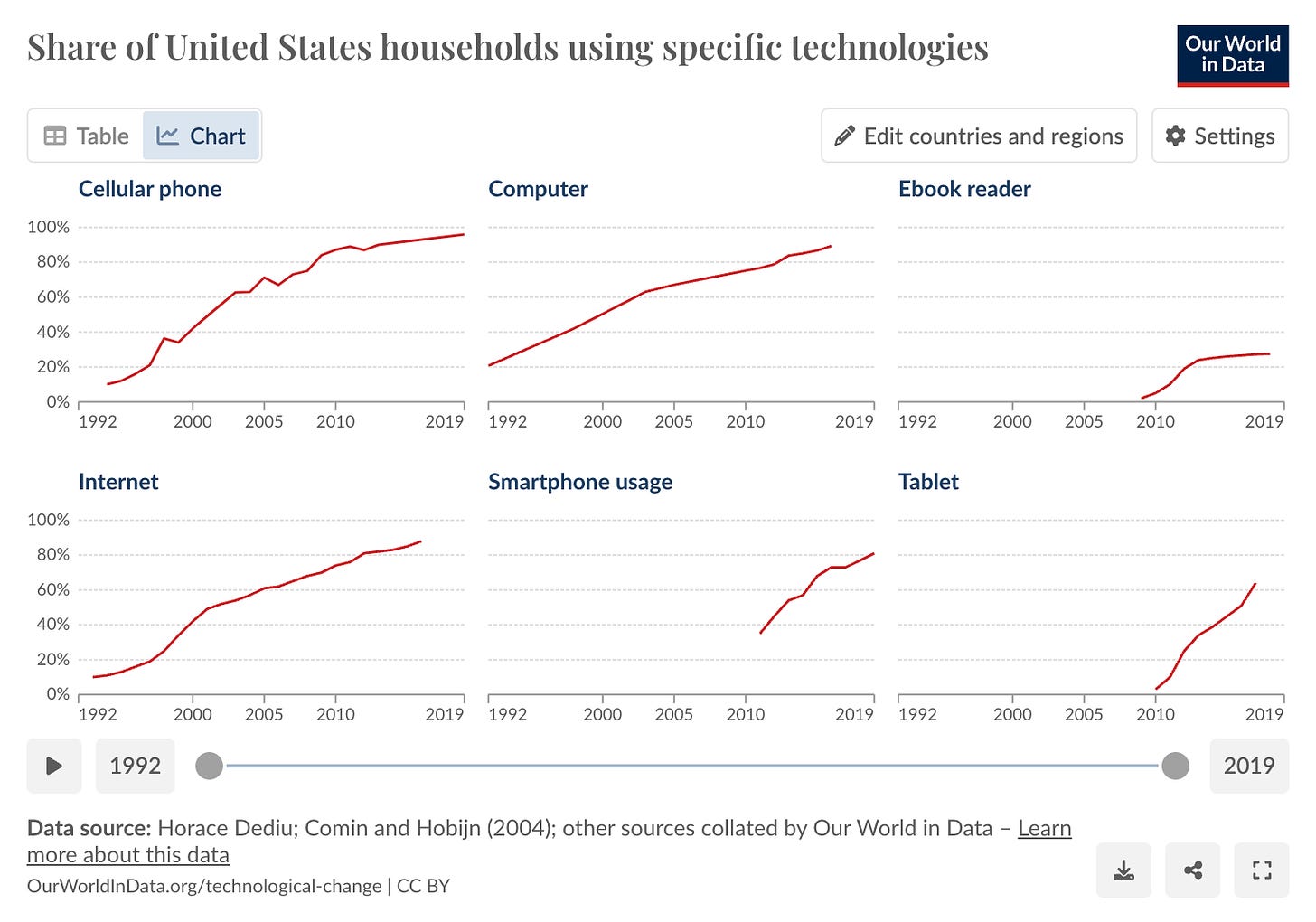

Other sectors look similar. Some communication technologies, like the cell phone, PC, and Internet, were adopted relatively slowly over the course of several decades. Building on that, smartphones and tablets started to dominate the market very quickly.

In a lot of cases, slow adoption was due to a combination of technical constraints and lack of perceived utility. The first PCs were incredibly expensive—the 1984 Macintosh cost $2,495, which is $7,300 in today’s dollars—and massive, but with a tiny screen, a problem shared by the mobile phone. Because of this, people struggled to perceive their utility, and reviews declared they were pointless and doomed. But tech advanced fast enough to keep consumer interest, and from today’s perspective, their adoption looks inevitable. At the time, this was hardly the case.

Some tech adoption has been rockier, with wild booms and busts. This is often because of a collision with fundamental technological limitations, like VR. VR development began in the 1980s, but we couldn’t make screens good enough or computers small enough to create viable consumer products, and after a boom that included arcade VR games and the short-lived Nintendo Power Glove, the tech went dormant in the consumer sphere. Over the ensuing decades, enterprise VR development continued, and combined with advances in computer and display technology, it became feasible to create a headset that won’t break your bank—or your neck. But a lot of the software still isn’t there—even Meta acknowledged its Horizon Worlds “metaverse” was too buggy for even employees to use—and the major question for VR is whether it will be able to ease into the slow-and-steady adoption cycle where the tech develops quickly enough to keep consumer and investor interest, or whether it’s about to fall into another trough.1

AI is another technology that has gone through development cycles. There was an initial boom of development from the 1950s to the mid-1970s in academia and government, prompting predictions that within a few years, machines would surpass humans in intelligence. Turns out, AI is hard, and there was an “AI winter” where funding dried up until the 1980s, when “expert systems” became all the rage. This time, lots of AI companies sprang up, but for a variety of reasons, including a lack of computing power and limited widespread utility, they went bust, and the second winter began. Finally, in the 1990s, AI began gathering steam again with DeepBlue’s chess victory and advances in computing power, deep learning, and generative AI brought us to the point we’re at now, undoubtedly a very hot summer.

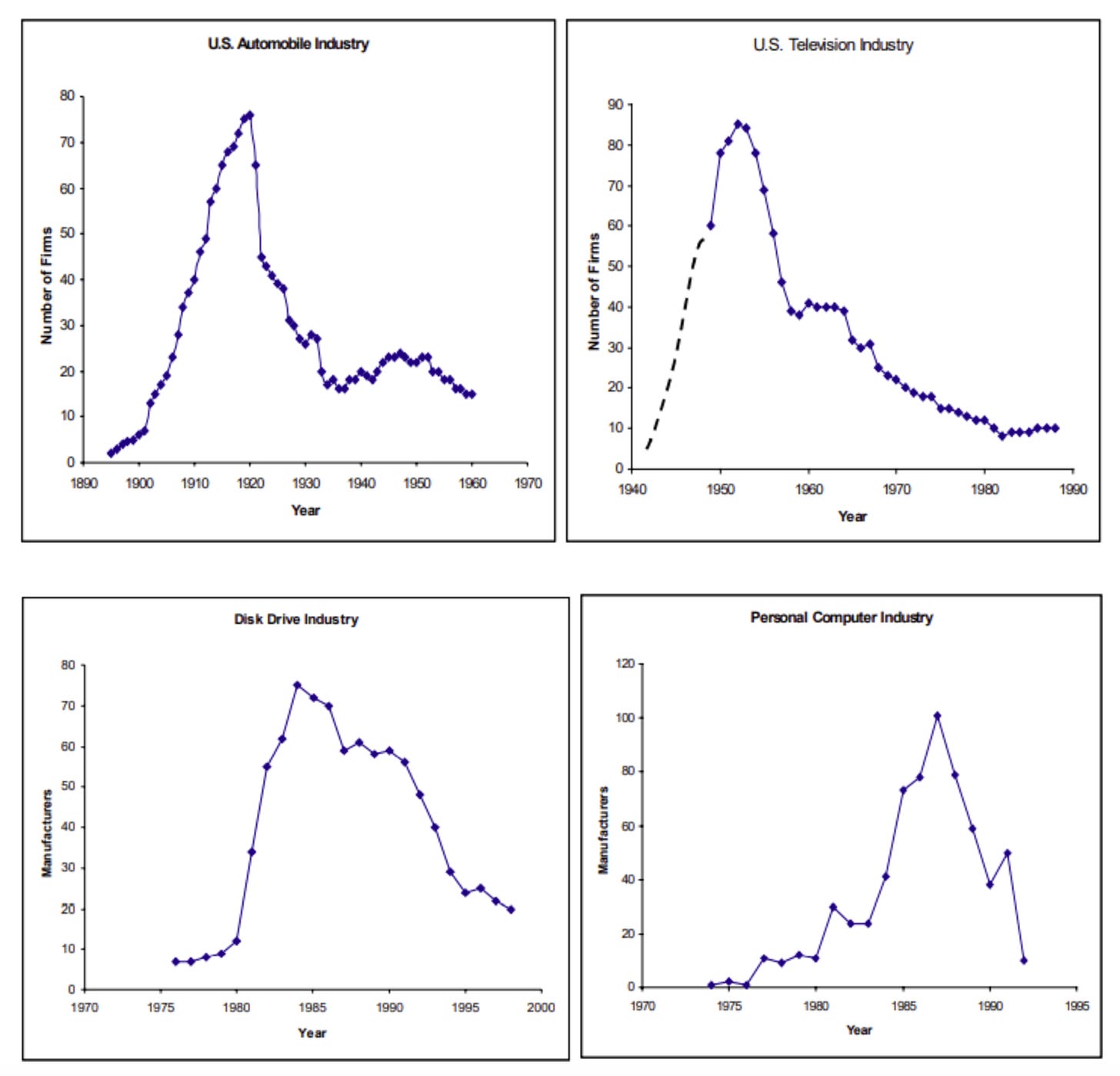

But we’ve seen this film before, and it’s had sequel after sequel over centuries. Going back to the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 1630s, when tulip bulb prices soared to 20 times the annual earnings of a carpenter, booms and busts have come and gone. In the UK in the 1800s, “Railway Mania” saw hundreds of new railroad-building companies spring up, only to go bust when everyone realized the UK couldn’t be one big rail track. And remember the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000?2 We still have the Internet, just like we still have railroads (and tulips). But the hype outstripped reality, causing investment to outpace what the market could actually support. This kind of boom-bust cycle is less because of the inherent utility of the item in question—or the actually pace of technological development—and more because of the hype surrounding it.

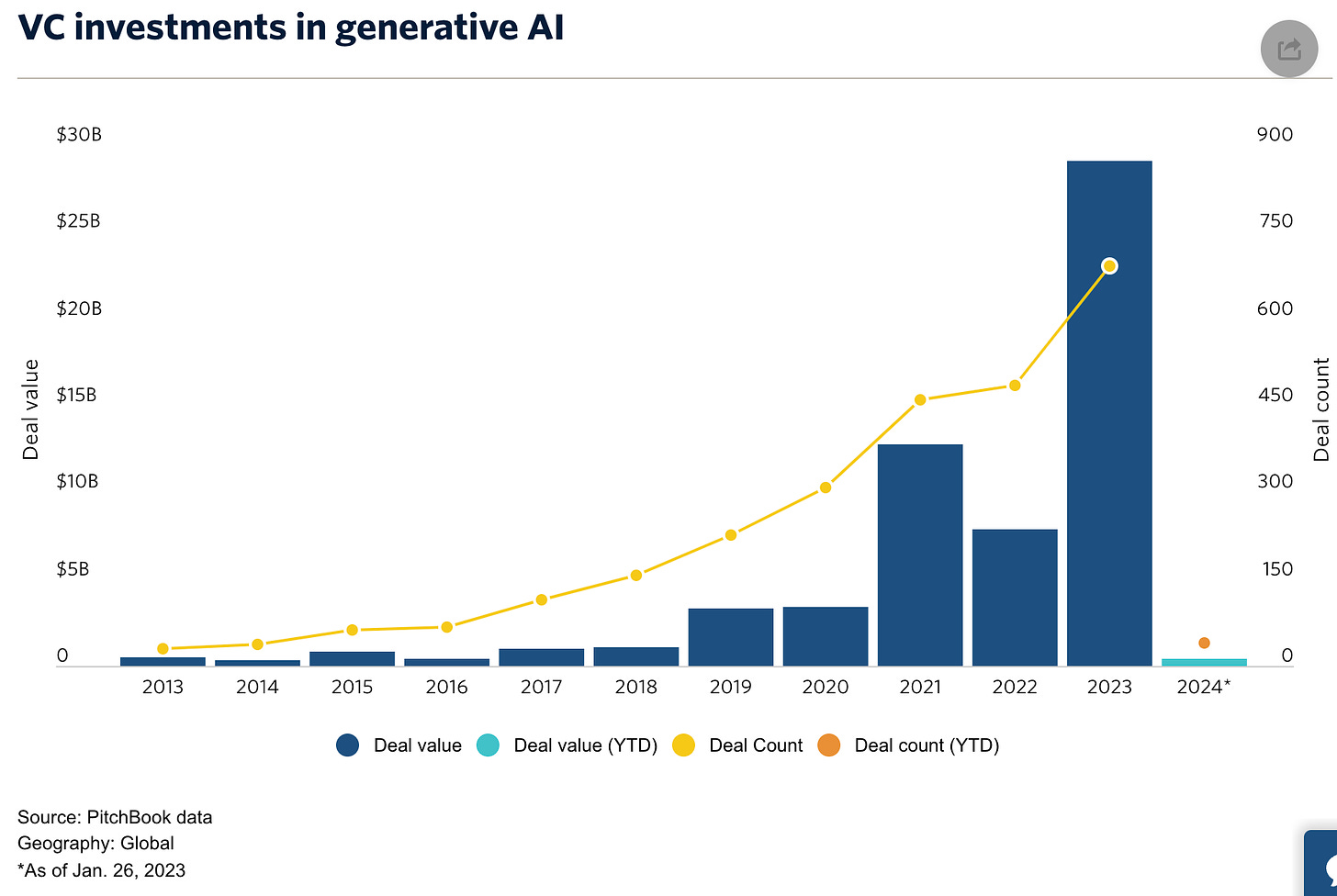

Even technologies that were adopted fairly smoothly, like cars and PCs, had economic bubbles pop, independent of the technological development underlying it. The thing with a bubble is that it doesn’t feel like one when you’re in it, but Kara Swisher has a wealth of experience with tech bubbles and thinks we might be in one. Despite a flood of investment, generative AI isn’t making money. OpenAI is making billions of dollars, but isn’t profitable; it costs an estimated $700,000 per day to run ChatGPT, and OpenAI is burning through hundreds of millions of dollars in R&D alone. Microsoft’s CoPilot is losing an average of $20 per month on each user, with some users costing Microsoft four times that. Some companies are compensating by increasing prices, like Google, which will charge $30/month for its enterprise AI productivity suite. The question, though, is whether people—and companies—will be willing to pay. ChatGPT usage is declining, and after the initial hype, it seems that a lot of people are questioning exactly how useful it is. For many people, it probably isn’t $30-a-month useful, and a lot of companies will also have a hard time justifying the expense. And yet, AI stocks are soaring, with chipmaker Nvidia up 77% this year after rising 239% last year. VC investment is also soaring, with almost $30 billion invested in generative AI in 2023, more than triple what was invested in 2022.3 Does this mean we’re in a bubble? I don’t know. But when industry players like Swisher and the CEO of Stability AI4 are saying we’re in one, we should be concerned. And what I do know is that history shows that even when tech is steadily adopted, the economic situation around it is not as stable.

Looking back on tech development, it’s easy to say that their success was inevitable, but this obscures the bumpy roads many had, and also the hype- and fear-mongers that accompanied them. Bicycles were certain to destroy public morality (especially when women started riding them). Violence on television and in video games was sure to cause kids to become violent. There’s also utopian dialogue: electronic Bulletin Board Systems and early Web were supposed to give us a disembodied utopia of communing minds. AI has both utopic and dystopic narratives, represented by the “effective accelerationists” (e/accs) who argue that AI will be so good for the world that it’s irresponsible not to develop it as fast as possible, and the “decelerationists” (decels) who think that AI development should slow down, plus the “AI doomers” who think it will destroy the world. E/accs believe that AI will lead to a post-scarcity utopia where AI unlocks such an abundance of resources that no one needs to work. AI doomers believe that AI will become a superintelligence that will create nanoweapons or super-viruses or otherwise destroy the world. On a high level, just like our narratives of smooth technological adoption, these seem appealing, and each camp has a lot of smart adherents. But these scenarios oversimplify the adoption environment. One doomer fear is a “fast takeoff” of AI that sees it, in a matter of days, exceed human intelligence, recursively improve itself, and take over the world. This—and many AI utopia scenarios—assume zero friction in adoption. And just like in high school physics class, that’s not actually the case. If it was, for one, breast cancer screening tools that can identify cancer years before doctors would be universally adopted. Instead, they’re bogged down in clinical trials, debates over hospital resource allocation, and questions about insurance coverage. Institutional inertia (it takes time to get groups to adopt new tools), technological friction (sometimes, there just isn’t enough compute), procedural friction (like clinical trials), and economic factors (like corporate bottom lines) all combine to slow the adoption of new tech.

So, where does this leave us? Hopefully, slightly less hyped about the development of AI. AI is an amazing set of technologies, and carries real potential to improve our lives, but also to make them worse. Still, this isn’t likely to happen all at once, even if adoption is fast, like the smartphone or microwave. Even as the tech improves, whether fast or slow, there will be economic ebbs and flows. But, my bet is that, in a few decades, we’ll look at all the ways AI is integrated into our lives and forget how it could have been any other way.

For the sake of my thesis, I hope it’s the former.

I don’t.

China had an AI startup bust in 2019, but generative AI seems to have revitalized the industry.

Emad Mostaque said this last year; he just stepped down from Stability AI to pursue “decentralized AI.”