ER 25: On Sugar, Social Media, and Dopamine

Or, why social media regulation is philosophically—if not factually—in the right place.

Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner! You know the drill: last Monday of the month, time for an extended piece. Today, we’re looking at the debate over kids and social media through the lens of how we regulate and stigmatize addiction. Not all addictions are stigmatized as much as others, so what does that mean for treatment and regulation? Let’s find out.

This edition of the Ethical Reckoner is brought to you by… the joys of packing your life into 50-pound suitcases.

Fun fact #1: Sugar is great. (In fact, I am eating a brownie as I write this.)

Not-fun fact #1: Refined sugar, in large quantities, isn’t great for our bodies. (In fact, this brownie is sweetened with dates. (It’s… fine.))

While there will always be a time and place for sweet stuff,1 the Dietary Guidelines for America recommend limiting added sugars to no more than 10% of your daily calories, and the World Health Organization sets its recommended maximum at 5%, warning that added sugars contribute to diabetes, obesity, and even cancer. And yet, we will always want sugar. Our bodies run on the simple sugar glucose, and our Paleolithic brains know that sweet foods are a good source of energy. What they don’t know is that we aren’t scavengers anymore, and we don’t need to gorge on a fortuitous honeycomb (or Oreos or whatever) because now there’s always another one right around the corner.

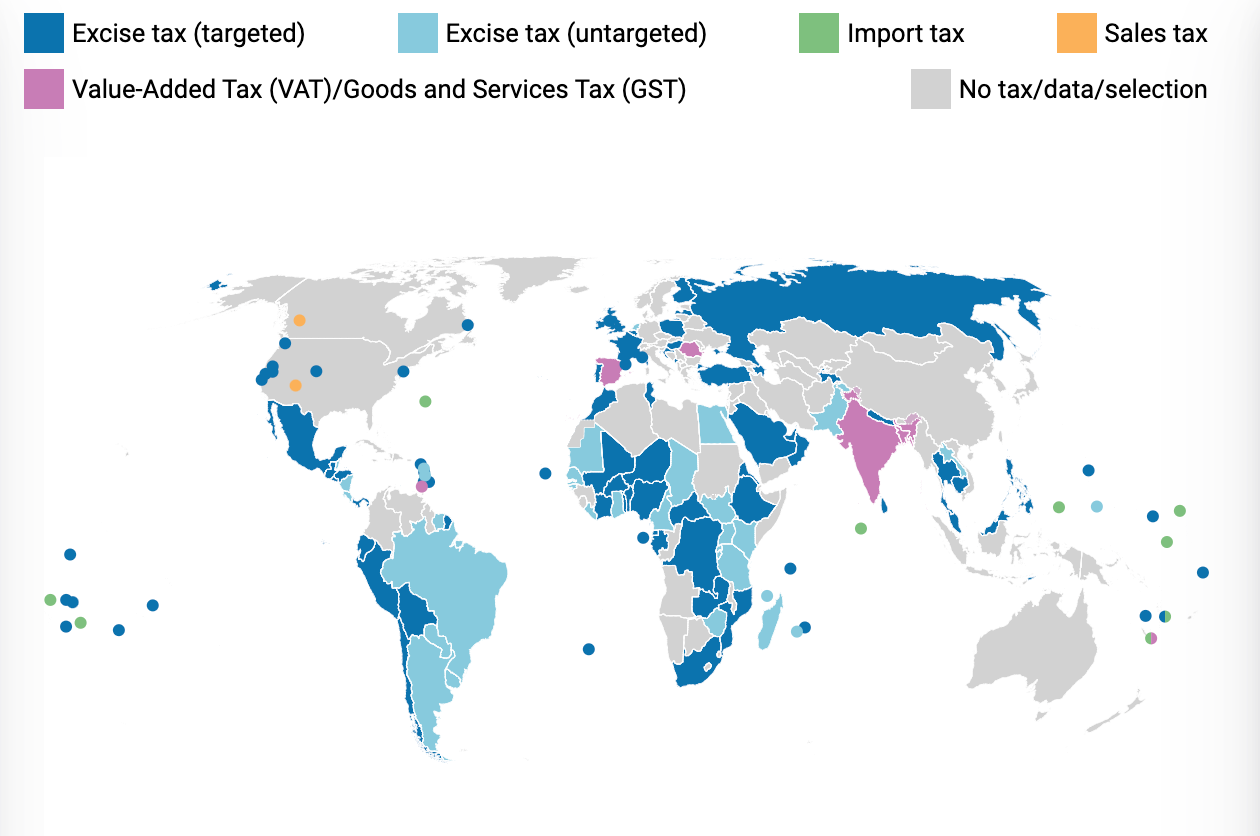

In order to “save” us from these baser instincts, jurisdictions worldwide are implementing taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (the primary source of added sugars in our diets). In the US, over 45 jurisdictions have instituted such taxes, and while the effects vary, on the whole such taxes seem to decrease the consumption of sugary beverages. New York City tried to go even further by banning the sale of sweetened beverages over 16 ounces, but the ban was struck down in 2014 by the NY Supreme Court on the grounds that the ban was not within the city’s regulatory power. The ban was wildly unpopular, with 60% of New Yorkers opposed. What has been more lasting have been taxes, with at least 54 countries including the UK, Mexico, and South Africa instituting taxes that led to decreases in sugary beverage sales.2

Why are we talking about sugar in a tech newsletter? Really, we’re talking about dopamine. Eating sugar releases dopamine, which reinforces reward pathways in our brains, which makes us want more, and so on. When the thing releasing dopamine is good for us, like hugging someone you love, then this is positive and beneficial reinforcement. When the thing releasing dopamine is bad for us, like injecting heroin, then this reinforcement is destructive.

But why are we talking about dopamine in a tech newsletter? Because guess what else releases dopamine? Using social media. Positive social stimuli activate our brains’ reward pathways, and social media is an essentially unlimited source of social stimulation. Social media platforms have even tinkered with how they issue notifications to get users to check in as often as possible.

Recently, there’s been a lot of scrutiny on social media addiction, in large part because of the release of a new book called “The Anxious Generation” by Jonathan Haidt. It argues that smartphones have “rewired” childhood away from play and towards “addictive” social media in a way that’s causing massive declines in teen mental health. The book has received a lot of attention, including praise from people who see their and their children’s experiences reflected in the book’s pages, but also criticism from academics and others who argue that the book’s claims doesn’t hold up when you look at the data. A lot of the debate comes down to arguments over statistical methods and study methods, and honestly, it’s bewildering. I’ve read the hot takes and listened to the podcasts, and everyone seems to be making statements of fact that are diametrically opposed. Basically, the impacts seem to depend on age, gender, kind of screen time, platform, other mental health issues, and probably a host of other factors. Still, it feels “truthy” that social media is bad for kids, and that narrative—helped by Congressional hearings chiding social media companies—have led to more proposals to protect kids from social media, including the defunct Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology (SMART) Act and the current Kids Online Safety Act (not to mention proposals in the UK and elsewhere).

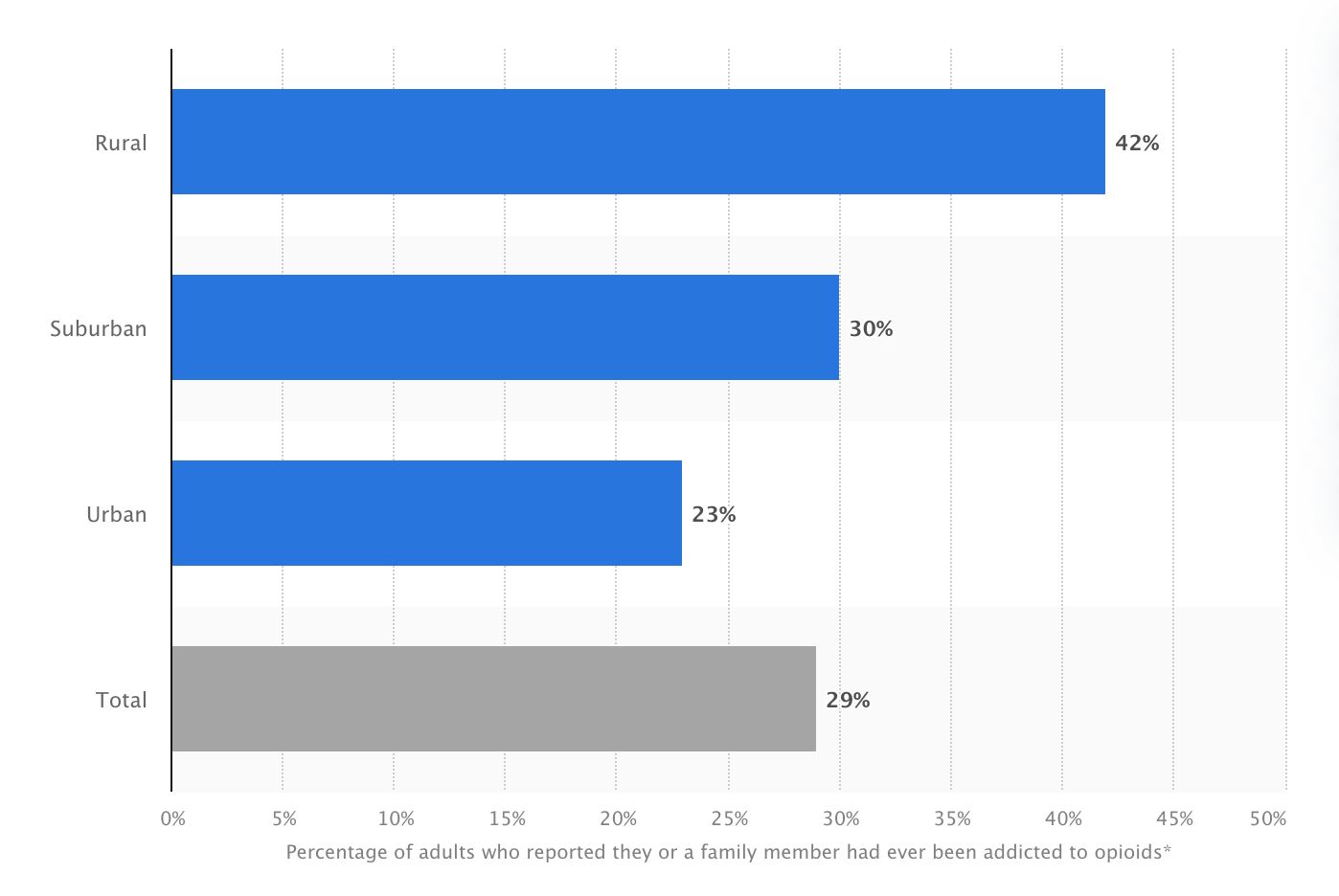

This level of action is unusual. We tend to regulate things that are addictive (alcohol, drugs, tobacco) and those are easy sells to the public because of the stigma surrounding addiction. Historically, we have seen addiction as an individual moral failing, especially in America. During the Prohibition era, the “temperance man” was lauded for having control over himself, with the corollary being that those who imbibed were seen as less moral. Even now, 78% of Americans believe that people addicted to prescription opioids are to blame for their addiction, and 72% believe that those addicted lack self-discipline. Higher stigma is correlated with support for prosecuting opioid users, which makes it less likely that they’ll obtain effective treatment. We certainly stigmatize weight as if people with obesity should just exercise more self-control, even though obesity is a complex issue with multifarious causes.

What’s interesting about the social media debate is that the stigmatization rhetoric is largely missing. We don’t blame kids who are suffering for spending too much time on Instagram. Instead, Big Tech has taken on the role of Big Tobacco, who were memorably dubbed “merchants of death” when their role in promoting tobacco addiction could no longer be ignored. However, this risks tipping over into a moral panic, where we act first and ask questions later. Rather than jumping to action (like the UK’s 1991 Dangerous Dogs Act, considered “among the worst pieces of legislation ever seen,” or unconstitutional attempts to ban violent video games), we need evidence. Many kids and teens genuinely like social media for more than just the dopamine cycle and find it useful for connecting with friends, expressing, and even things like marketing themselves as student-athletes. Any regulation has to take into account the knock-on effects for kids and teens beyond just generic freedom of expression concerns (although this is important too). I don’t think existing legislation and proposals do this enough, but we could gather more data, which is something both sides of the debate get around. My former Oxford professor, Andrew Przybylski, who has criticized Haidt’s arguments, also warns against legislating without evidence. Haidt acknowledges that we need more evidence; an interview with Kara Swisher, Haidt proposed a smartphone-free-school trial—take similar schools, make some phone-free, leave others the same, and see what happens—and that would be an interesting experiment if it could get approved. (Turns out it’s hard to run experiments on kids.) I wonder if teens self-organizing experiments could also produce some useful data; if enough kids went off social media and were willing to log data about their mental health and then hand it to a researcher, there could potentially be some interesting data (or absolute garbage). Regardless, we need more than just correlative data; the many correlative and few causative studies is part of what’s gotten us in this muddle in the first place.

Even if social media does turn out to be addictive, harmful, and deserving of regulation, we still need to move from a model of regulating addictive things to regulating contributors to public health crises. In that way, social media regulation has been helpful because it shows us how to regulate things that we think are addictive with less moralization and stigmatization. We are concerned about social media because of its effects on their mental health, and we know that blaming kids for getting hooked on it isn’t helpful. We don’t take the same attitude towards other addictions, although it’s important to note that things like sugar and social media aren’t addictive in the traditional sense. They have similar dopamine actions, but we aren’t physically dependent on them like people can be on drugs. Rather, they are contributors to other public health crises: obesity and diabetes in the case of sugar, potentially loneliness and polarization in the case of social media. Sugar is often rhetorically cast as an addiction, partly to increase support for trying to decrease consumption, but this comes with an implied permission to demonize so-called addicts via fat shaming and other attacks. Stigmatization also places a ceiling into how willing policymakers are to address addictions of all types—when push comes to shove, resources will be shifted away from people living with addiction because they are seen as having brought their condition on themselves. Shifting the frame to addressing the effects as a public health crisis also widens the potentially impacted audience—it becomes a societal issue that could impact anyone and thus demands a society-wide approach.

Even after making this shift, we can still regulate traditionally addictive things. For instance, opioid overdoses are a public health crisis, as are the health impacts caused by smoking, alcohol abuse, and other drugs. This is a more humane concept of regulation, as by focusing on the public health impacts rather than the individual addiction, we are obligated to treat those impacted as victims in need of medical assistance, rather than as morally inferior or criminal.3 There are lots of efforts along these lines regarding drug addiction, but they face headwinds due to the aforementioned stigmas against addiction and using public resources to address it—though we use an enormous amount of public resources on imprisoning people for drug offenses, so why not dedicate those resources to helping people get well?4

This approach creates a more unified model of regulating contributors to public health crises (and potential public health crises) with a range of approaches. From the sugar example, we have warnings (dietary recommendations and PSAs), deterrence (taxes), and bans (NYC’s law). From smoking and alcohol regulations, we also see age gating (in the US, the age to buy tobacco is 18 in most jurisdictions, and 21 for alcohol). Some things, like marijuana, are subject to a combination of approaches—there are public health campaigns against marijuana, which is illegal federally and in many states, but some states and jurisdictions have legalized it subject to age restrictions and heavy taxes.

Going back to social media, we do ostensibly age-gate it; 13 is typically the threshold for getting an account, though it’s incredibly easy to lie about your birthday. Instagram proposed some different age verification tools in 2022, including submitting photo ID, submitting a video selfie that AI would analyze to determine the person’s age, and asking friends to vouch for a user. While we should have methods other than submitting a photo ID to allow kids who can’t obtain one to access platforms, the latter two are questionable—AI can’t tell the difference between a 17-year-old and an 18-year-old, and kids are smart and will figure out how to “age up” for the algorithm anyway. They’ll also get their friends to lie for them. And ultimately, these are useless because the only situation they are proposed for use is when a user tries to change their age from under 18 to over 18 to access adult content—so kids will just create accounts with their fake age off the bat (a time-honored Facebook tradition). We should have more effective age gating to protect kids and teenagers, and also explore changing algorithms for younger users to prevent them from falling deep into harmful content. The Kids Online Safety Act, while controversial, might help with these.

ER 22: How in tarnation do we keep kids safe online?

Wholesale bans, like NYC’s soda ban, will probably be overly paternalistic5 and too unpopular to be workable—although we’ll see what happens with Florida’s under-16 social media ban—but deterrents could be effective. We could tax platforms based on their perceived societal impact. We could make them build in guardrails to nudge users off the platform after certain amounts of time (as proposed in the SMART Act6). We could make them design their platforms to be less enticing. A TechCrunch article proposed putting this authority into the hands of the FDA, which has the authority to regulate drugs as “articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals.” The article argues that the algorithms that control social media platforms fall under this as an article that alters our brains. This could be expanded internationally through a variety of international venues that the FDA engages with. Existing efforts like the EU’s Digital Service Act and Digital Market Act promise to curtail platforms’ power and may mitigate some of the impact of these platforms, but there’s little regulation targeted specifically at the public health impacts of social media platforms.

This is all predicated, though, on the assumption that we get good data about what is making our children and teenagers so miserable and that it—or a significant part of it-—turns out to be social media. Regardless, the idea that we can regulate something we perceive to be an addiction because of its public health impacts without stigmatizing the affected people is something we need to emphasize as we explore how to help people suffering from other forms of addiction. Because sometimes, we can’t Just Say No.

Case(s) in point: lemonade in a sun-sweaty glass with clinking ice cubes; ice cream dripping down the cone on the first day it finally feels like summer; hot chocolate (always marshmallow) when your nose is pink from the cold; a marshmallow toasted over fire, grill, or stove; a lollipop after a shot; a spoonful of cookie dough; birthday cake. I could go on.

Many studies have been done to determine if sugary beverage taxes actually decrease consumption, and the general consensus seems to be that it does, unless the tax is easily skirted by leaving the jurisdiction—in Philadelphia, many people have begun buying their soda just outside the city limits to avoid the city’s 1.56 cent/ounce tax.

I am imperfectly parroting what many in the public health community know far more about and have been saying for far longer.

If this seems to be conflating addiction and criminality, well, that’s exactly what America’s criminal justice and mental health systems do.

China has been successful in issuing fairly paternalistic regulations, including limiting the amount of time youth can play video games. However, due to philosophical and political differences that we don’t have the space to get into in a footnote, this approach is more workable there.

The SMART Act was not an especially good bill for a variety of reasons. The bill tried to ban infinite scroll and autoplay, as well as automatically limit a user’s time on a platform to 30 minutes a day (which the user could change, but would have to set monthly). I agree with my former professor Andrew Przybylski, who said that the bill was “silly and practically unworkable” and may have distracted from better legislation.

Thank you very much to Jackson for providing comments on a (much, much earlier) version of this draft.

Thumbnail image generated by DALL-E 3 via ChatGPT with the prompt: “Please make me a brushy, abstract impressionist painting of the concept of sugar addiction in pale shades of blue and gray.”