Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. It’s the last week of the month, so we’re taking a break from the news (well, at least the news as told by the Weekly Reckoning) for the original format of the newsletter. This week, a history of media in elections, and whether this year will be the election of memes.

This edition of the Ethical Reckoner is brought to you by… the joy of watching random sports in the Olympics.

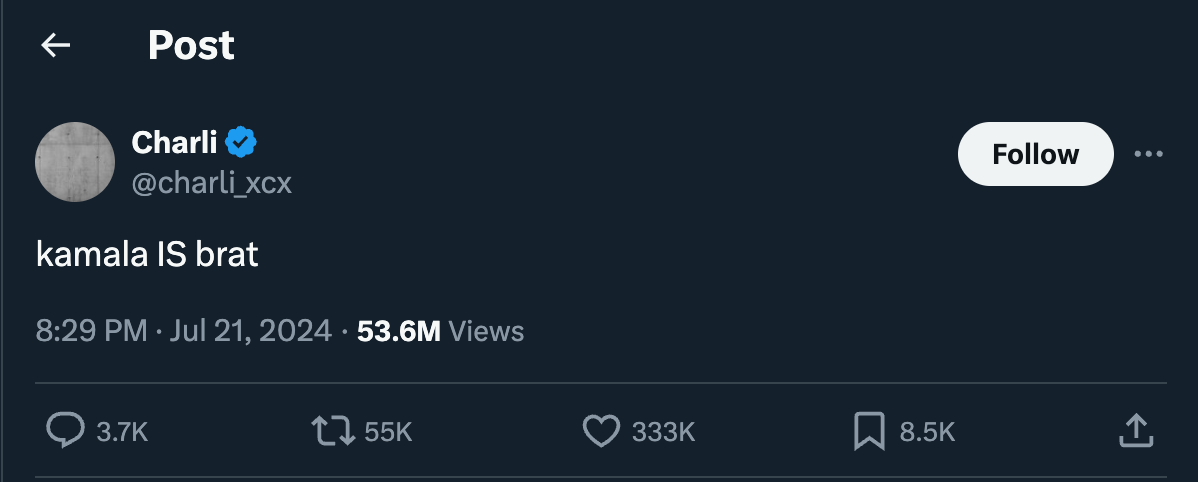

If you’ve been on the Internet for more than five seconds in the last week, you’ve probably encountered content involving Kamala Harris and a coconut tree, or the Charli XCX album Brat, or maybe something about being “unburdened by what has been.” This last week has been a fantastic one for Internet content, specifically political memes involving Kamala Harris. It started on July 21, the day after Biden announced he was stepping aside as the Democratic nominee for the presidency, when Charli XCX tweeted “kamala IS brat”.

Brat is Charli XCX’s new album, which has been wildly popular in “pop girl summer.” Being “brat” (crucially not “a brat”1) means you’re a “girl who is a little messy and likes to party and maybe says some dumb things sometimes,” and Harris’s tendency for amusing tangents about Venn diagrams and slightly perplexing but actually thought-provoking quotes about how you haven’t just dropped into this world “out of a coconut tree” but exist “in the context of all in which you live and what came before you” make her seem like the kind of kooky aunt that you would have a margarita (or six) with. Her campaign has embraced it, updating their campaign headquarter Twitter bio to imitate the cover of Brat:

And so the memes have been coming thick and fast, raising the question of whether this is the “meme election" where memes will be a critical factor.

We’ve had elections defined by media before. 1924 was the radio election (the great paper “Radio’s Political Past” details this well). Calvin Coolidge, though not as talented an orator as his opponent, John W. Davis, had a party behind him that understood the potential importance of radio. The Republican Party started adopting speeches to radio and outspent the Democrats three to one on radio campaigning. As a result, their messages were heard 3-4x more often than Democrats, and Coolidge won the election in a landslide (382 electoral votes to Davis’s 136). Radio continued to be important in subsequent elections; in 1932, FDR demolished Herbert Hoover because FDR sounded personable on the radio and created a sense of intimacy through his “fireside chats.” By comparison, Hoover sounded like “an old-fashioned phonograph in need of winding.” This established a trend: the politicians that first adapted to new media, and those that then mastered it, excelled. And while correlation is not causation, “excelling” has historically meant “winning their election.”

1952 was the television election. Eisenhower, though he didn’t come across particularly well on TV, launched an extraordinarily successful series of TV ads, including the now-famous “I like Ike” ad.

(Good luck getting this out of your head.)

Though Eisenhower likely would have won without his TV efforts, this kicked off a trend where candidates had to spend on paid TV advertising, starting the political money arms race.

In retrospect, maybe we don’t like Ike.

JFK then went on to be the TV master; in 1960, a televised debate where JFK appeared calm, cool, and collected may have swung the race to him over Nixon, who was sweating and “looked as if they had him embalmed before he had died.” As president, he was the first to hold televised press conferences, and his charm endeared him to the press and the American people (and may have launched the era of appearance politics, which was easy for JFK since he looked like he did).

2008 was the first social media election. In 2007, Obama was a senator from Illinois with little name recognition and down double digits in polls. But his “New Media” team (made up of mostly people in their 20s) launched a sophisticated operation that leveraged email, SMS, and, most importantly, social media—both the existing platforms and the campaign’s “MyBO” organizing platform—which let the Obama campaign reach more voters in grassroots campaigning and project “authenticity.” They used voter and engagement data to push events close to people and A/B test different messages, which seemed especially helpful with the youth vote. Obama got 66% of the youth vote (an all-time high for Democrats; compare to John Kerry’s 54% in 2004) and beat McCain (whose social media strategy can be summed up in a single unsourced Wikipedia sentence) 365-173.

![Screenshot of a section of McCain’s 2008 campaign wikipedia page Initial stages[edit] By a few weeks prior to making his announcement on Letterman, McCain was already beginning to trail behind former Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani in the polls, a situation attributed to his steadfast support for the Iraq War troop surge of 2007.[33] In March 2007, with considerable press attention and in hopes of reigniting his efforts, McCain brought back the "Straight Talk Express" campaign bus that he had used to much positive effect in his outsider run in 2000.[34] The following text is highlighted: Like many candidates, McCain took to the internet in order to help boost his campaign; appealing to younger audiences by creating Facebook and MySpace pages, along with an account on YouTube.[citation needed] There is also a photo of McCain standing next to a white male reporter taking notes on a notepad: Senator John McCain interviewed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, prior to the ribbon cutting ceremony of The Center for the Intrepid, a $50 million physical rehabilitation facility designed for servicemembers wounded in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. January 29, 2007. Screenshot of a section of McCain’s 2008 campaign wikipedia page Initial stages[edit] By a few weeks prior to making his announcement on Letterman, McCain was already beginning to trail behind former Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani in the polls, a situation attributed to his steadfast support for the Iraq War troop surge of 2007.[33] In March 2007, with considerable press attention and in hopes of reigniting his efforts, McCain brought back the "Straight Talk Express" campaign bus that he had used to much positive effect in his outsider run in 2000.[34] The following text is highlighted: Like many candidates, McCain took to the internet in order to help boost his campaign; appealing to younger audiences by creating Facebook and MySpace pages, along with an account on YouTube.[citation needed] There is also a photo of McCain standing next to a white male reporter taking notes on a notepad: Senator John McCain interviewed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, prior to the ribbon cutting ceremony of The Center for the Intrepid, a $50 million physical rehabilitation facility designed for servicemembers wounded in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. January 29, 2007.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F190c542b-8438-4c59-a108-a4e59443e1de_1762x722.png)

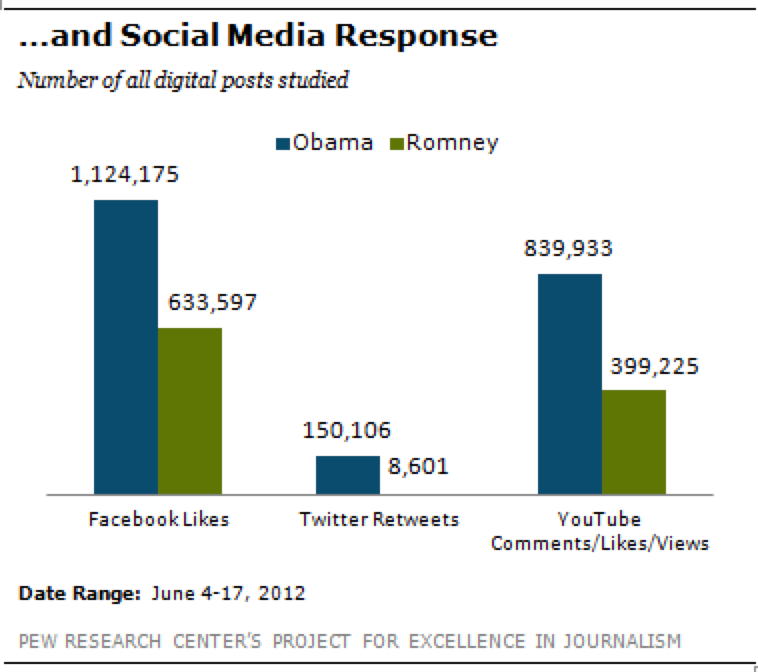

Obama was both the first to adapt to social media and genuinely good at it. By 2012, social media had evolved a lot, but Obama’s digital strategy adapted and had much more engagement than Mitt Romney’s.

One thing neither campaign did much of was make use of the “social aspect of social media,” meaning they rarely engaged with content posted by other people, instead using it more as a campaign megaphone. Trump, on the other hand, used Twitter as a more-or-less unfiltered platform during the 2016 campaign to attack his enemies and promote himself, frequently engaging with flattering content from outlets like Fox News. It allowed him to “detour around news media gatekeepers,” making the medium the message: “I’m talking directly to you as part of my fanbase through Twitter because the mainstream media wants to quash my message.”

Neither Trump nor Biden totally mastered the meme. The Biden campaign came closest with its embrace of “Dark Brandon,” but that’s faded as Biden’s become feebler. Now, Harris has a chance to reshape the race both through what’s now “traditional” social media campaigning but also through meme mastery.

The thing with memes is they can’t be forced. The Kamala campaign couldn’t have manufactured this moment; it had to occur organically. As Kevin Roose wrote, “Memes work better when their subjects are only superficially aware of them, and certainly not when they’re part of an official campaign strategy.” When you try to force it, that’s when it becomes cringe (see Hilary Clinton’s “Pokemon Go to the polls” moment). The question over how many winking references are allowed hasn’t been settled (though is likely between zero and one). Commentators agree they have to “play it cool;” “If V.P. Harris starts wearing merch with coconuts on it, that might be a bridge too far.” In that way, memes are distinct from other forms of media in that they are not a team of horses to be harnessed, but a wave to be ridden.

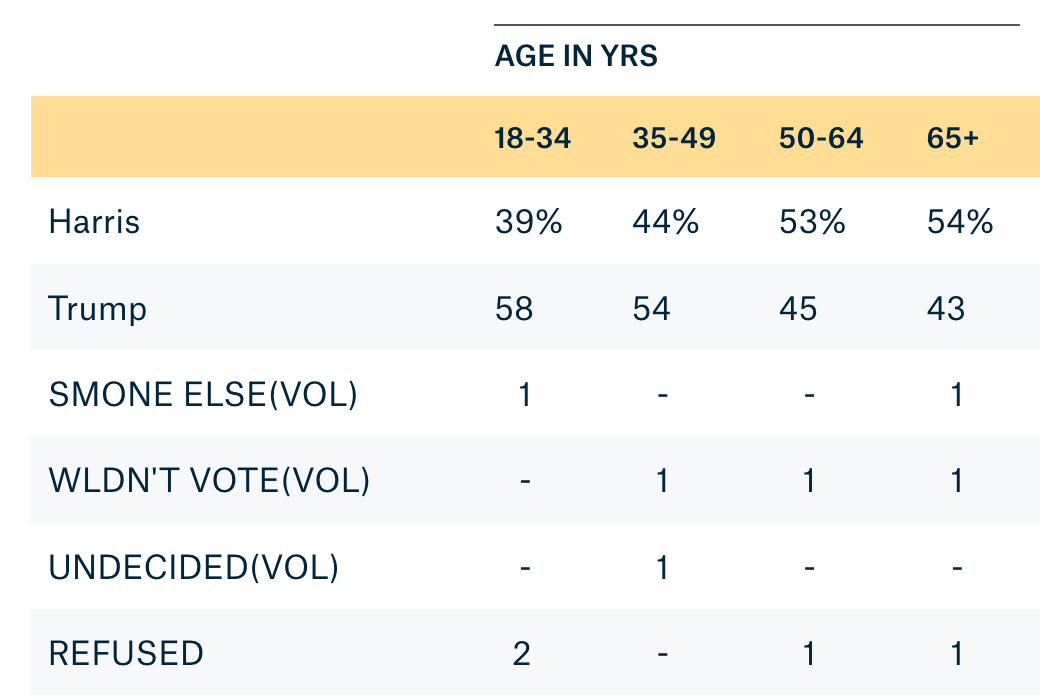

However, there are things the campaign can do to keep the wave going. Liberal meme-makers are palpably excited about Harris’s candidacy, with one saying, “with Biden we were trying to manufacture excitement from vapor.” Harris can keep being memeable and keep carefully winking at those memes, but her social media strategy shouldn’t only be to surf the meme wave, because you never know when it will dissipate (or crash on top of you). But, like Obama in 2008 and 2012, social media will be crucial. In a poll conducted from July 19-21 (so just before and just after Biden announced he was dropping out) a hypothetical Harris-Trump matchup saw Harris trailing with voters 18-34 by nineteen points. But maybe a good social media strategy will get the young voters more “coconut pilled.”

Anyway, what can we learn from this? The first is that the first presidential candidate to arrive at a new communication medium has always won the election. The second is that subsequent candidates who master a medium also benefit, but eventually basic competence is expected. And the last is that memes may be a potent political tool, but they’re not one that can be harnessed—although memeability may be a new skill for candidates.

Eulogies are already being written for Brat Summer. Memes are transient and fickle things, and Internet culture can turn on a dime. But if Harris can keep her cool—and stay cool (I’m sorry, fire2)—memes might just become a key tool as she tries to turn her social media campaign into a winning presidential campaign.

Calling someone “a brat” invokes the dictionary definition of “an ill-mannered annoying child.” Calling someone “brat” means they embody the spirit of the album Brat: irreverent, fun-loving, a bit brash.

”cool” is no longer cool.

Thumbnail generated by DALL-E 3 via ChatGPT with the prompt “Make an abstract, brushy, Impressionist painting in blues and reds representing the concept of media evolution.”