ER 29: On the romanticization of disconnecting

Or, why I long to return to my childhood tradwife farm camp.

Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. It’s the last Monday of the month (how did that happen?) so we’re back to the original format. Today, we’ve got a short wander through some ideas about digital detoxes and how “disconnecting” is both a valuable and extremely privileged thing to do.

This edition of the Ethical Reckoner is brought to you by… the Kind bar that saved me after a monkey stole my breakfast.

A few days ago, I returned from Rio de Janeiro, where I was attending a friend’s wedding. Rio is an amazing city, in no small part because of the nature that’s all around it. One morning, I hiked up to Christ the Redeemer, a forested path climbing up a mountainside to the statue. I was hiking alone and was early enough that I was the first one to sign in (and thus on cobweb-clearing duty).1 AllTrails estimated that it would take 4.5 hours to make the 7 mile round trip. I love hiking. I also love podcasts and perpetually have a long queue of podcasts for whenever I’m walking essentially any distance. But I also do some of my best thinking when walking without anything else in my ears, so I’ve been consciously carving out walks where I don’t listen to anything.2 And though I had my AirPods in my daypack, as I took in the chirps of unfamiliar birds and gentle clicks of insects, it seemed wrong to drown them out with one of my many tech podcasts. So, smugly, I thought to myself, “I’m going to have an unmediated hiking experience” and left my headphones in my bag.

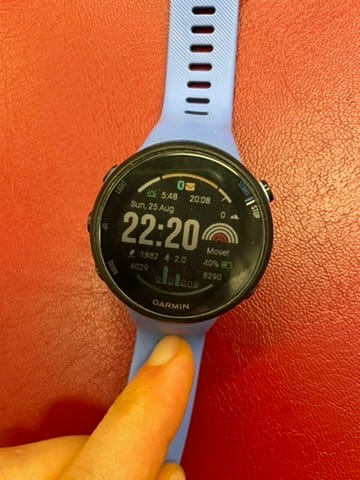

I quickly realized the irony of this thought as I glanced down at my running watch, felt my phone in my pocket, and tallied up the number of apps tracking my pace and/or location: Garmin Connect through the watch (which would later feed into Strava), plus AllTrails (so I wouldn’t get lost), Peloton (just because), and whatever apps I haven’t locked down location permissions on well enough that are probably selling my location data to who knows what companies. While my hiking experience may have been unmediated by my audio apps, it certainly wasn’t disconnected. These apps were still tracking and datafying my experience, transforming that experience of moving through the forest into a series of metrics—which I appreciated when they told me I’d completed the hike in three hours flat. But it was hardly the low-tech experience I patted myself on the back for.

Tech3 by and large has two functions: it connects us (to each other and to the Internet), and it datafies our experiences. In doing so, it mediates how we experience the rest of the world. I’m less aware of my surroundings when streaming a podcast. I think differently about a hike when I see my route and pace on a screen. This can be useful—I can look up a training plan for a race online and then track my training runs and progress in an app—but can also be overwhelming; I turned off all sorts of features and notifications on the watch and decided to only wear it while exercising because I don’t want all the rest of my time datafied and broken down into steps and “body battery” metrics and prompts to stand up.

I’ve been thinking about the idea of disconnecting recently. Amidst the debates over privacy and kid’s online safety and a million other things, there’s a pervasive sense that we feel like we should be using less technology, or at least technology less. “Digital detox” discourse persists, and there’s a million and one gadgets (and, ironically, apps) designed to help you use your phone less. I was thinking back to a sleepaway camp I went to as a child, on a farm in the middle of Ohio’s Amish country. No one was allowed phones (although I don’t think I had one at the time). I don’t think there were even clocks around. We slept when it was dark, woke up with the rooster—depending on how many crows you slept through, you might get to milk the goats—and then fed the chickens, baled hay, and cut thistle during the day.4

I wonder if wanting to return to the farm is my own manifestation of the “tradwife” movement, which promotes a return to a simpler (and deeply problematic) model of the home and gender relations. I find the tradwife lifestyle deeply ironic because even though they’re presenting a lifestyle centered around a traditional domestic bliss from an idealized vision of a lower-tech past—these women are making cinnamon rolls from scratch in gingham dresses, not vlogging about technology or current affairs—the tradwife movement was born and lives on TikTok, making it both an inherently connected lifestyle and one mediated by the need to be appealing online even as they’re kneading bread by hand and promoting a return to an age before computers existed.

As much as I sometimes want to return to that farm, I know that I’m seeing it through rose-colored glasses. Technology is a great thing. Sure, it’s enabled massive economic and productivity gains, etc etc, but also, I would perpetually be lost without Google Maps, a lot lonelier without FaceTime and WhatsApp, and a lot less employed without my laptop. Before starting my PhD, I literally coded for a living. But on a walking tour in Rio, I looked at Google Maps to situate myself, and found something astounding: the narrow alley we were in didn’t appear on the map. Nor did many others; only the main roads were marked. Rio is absolutely not a disconnected city—everyone, even street vendors, has contactless card machines—but even Google Maps doesn’t know everything about it, removing one element of mediation from the equation.

Sometimes we want this mediation, sometimes we don’t. This is illustrated in a tale of two towns and how they reacted to Google Street View. In 2009, a UK village Broughton blocked a Google Street View from entering their village: the villagers were concerned about privacy and crime and vowed to not let the Street View car in. When it arrived, one man “rushed round banging on neighbours’ doors, and soon had a posse surrounding the driver,” who beat it when the police—firmly on the side of the protestors, it seems—were called. By contrast, the tourism board of the Faroe Islands, which in 2016 was not on Street View, thought that getting themselves added would help drum up tourist interest. They decided to take matters into their own hands by strapping cameras to sheep and uploading the resulting image to Street View. This caught the attention of Google, who sent actual Street View cameras to replace “Sheep View”—although they said that “the tourism board decided to leave some spots out to preserve a bit of the islands’ mystery.” These show a different dynamic than my Garmin watch. While we can make individual choices about our own tech use, sometimes there are times when collective action is necessary.

Even though one group wants in and one group wants out, both are trying to exert some sort of control over their digital footprints. Some don’t have this choice, though. Nearly 3 billion people have never used the Internet. While we may romanticize a “low-tech lifestyle,” these people have less access to education, information, and all the other benefits of technology. Still, the rest of us have to deal with the consequences of digital technologies: lowered attention spans, possible mental health issues, privacy invasions, etc. On the whole, though, it’s safe to say that the benefits outweigh the cons.

There’s a privilege in disconnecting, in a digital detox, when that comes with the promise of being able to reconnect at the end of it. And in some ways, there are advantages to not being datafied. But there’s also a whole lot of inconvenience to being disconnected and a lot of benefits to being on grid (which the tradwives can never fully acknowledge lest they undermine part of their message). And from this privileged Western perspective, it’s easy to wish for a “simpler” life without fully acknowledging how lucky we are to have access to all this tech. But that doesn’t mean we have to unquestioningly accept it and its impacts. Like the Faroe Islanders, we can welcome it when it helps us, while pushing it away when it doesn’t like the residents of Broughton. But in order to do this, we need to be aware of how we’re using it, to think for a moment before we drown out the birdsong with our headphones and download yet another app.

I stayed within shouting distance of a British couple that started right after me, don’t worry @family. And yes, this is the hike where the monkey stole my breakfast.

Then the challenge becomes not checking my phone, but that’s another story

We’re talking networked consumer technologies here, not technologies like the wheel and the pencil.

Honestly, “paying labor” is a genius business model.

Thumbnail generated by DALL-E 3 via ChatGPT with the tree bark photo and the prompt “Take this photo and turn it into an abstract brushy watercolor painting”.