Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. You know the drill: last Monday == the original longread. This week, we’re putting the soap opera-levels of drama at OpenAI in context, discussing why we need to think about it not as a company, but more akin to a band like the Beatles—Beatlemania, breakup, and all. Besides being an interesting thought experiment, I think this can help us think about what we might expect from a new breed of AI start-ups.

This edition of the Ethical Reckoner is brought to you by… pancakes with friends

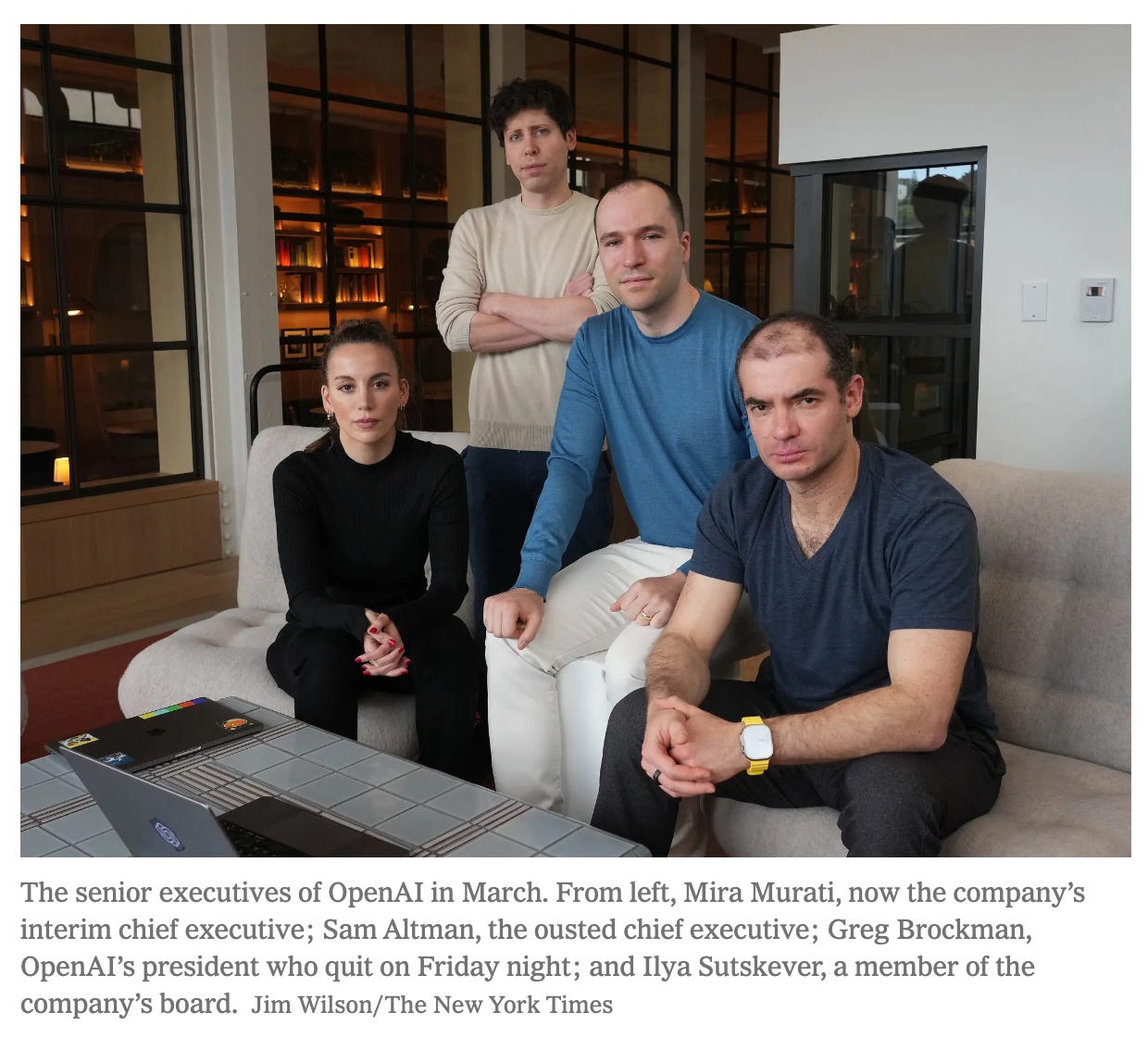

OpenAI has been going through a lot recently. To start, last November, there was an attempted coup that ousted co-founder and CEO Sam Altman… for all of five days. After an internal and external uproar, he was reinstated, and the board members who had tried to fire him (for reasons never clearly articulated) were replaced. Then in February, the exodus began: co-founder Andrej Karpathy quit. In May, Ilya Sutskever (another co-founder who was OpenAI’s chief scientist) resigned. In August, two more co-founders either quit or went on leave. (At this point, only two of OpenAI’s thirteen co-founders are still with the company: Sam Altman and language/code generation lead Wojciech Zaremba.1) And then last week, CTO Mira Murati (the only woman in OpenAI's c-suite), plus the chief research officer and VP of research announced they were quitting, which was immediately followed by news that OpenAI was going to stop being a non-profit.

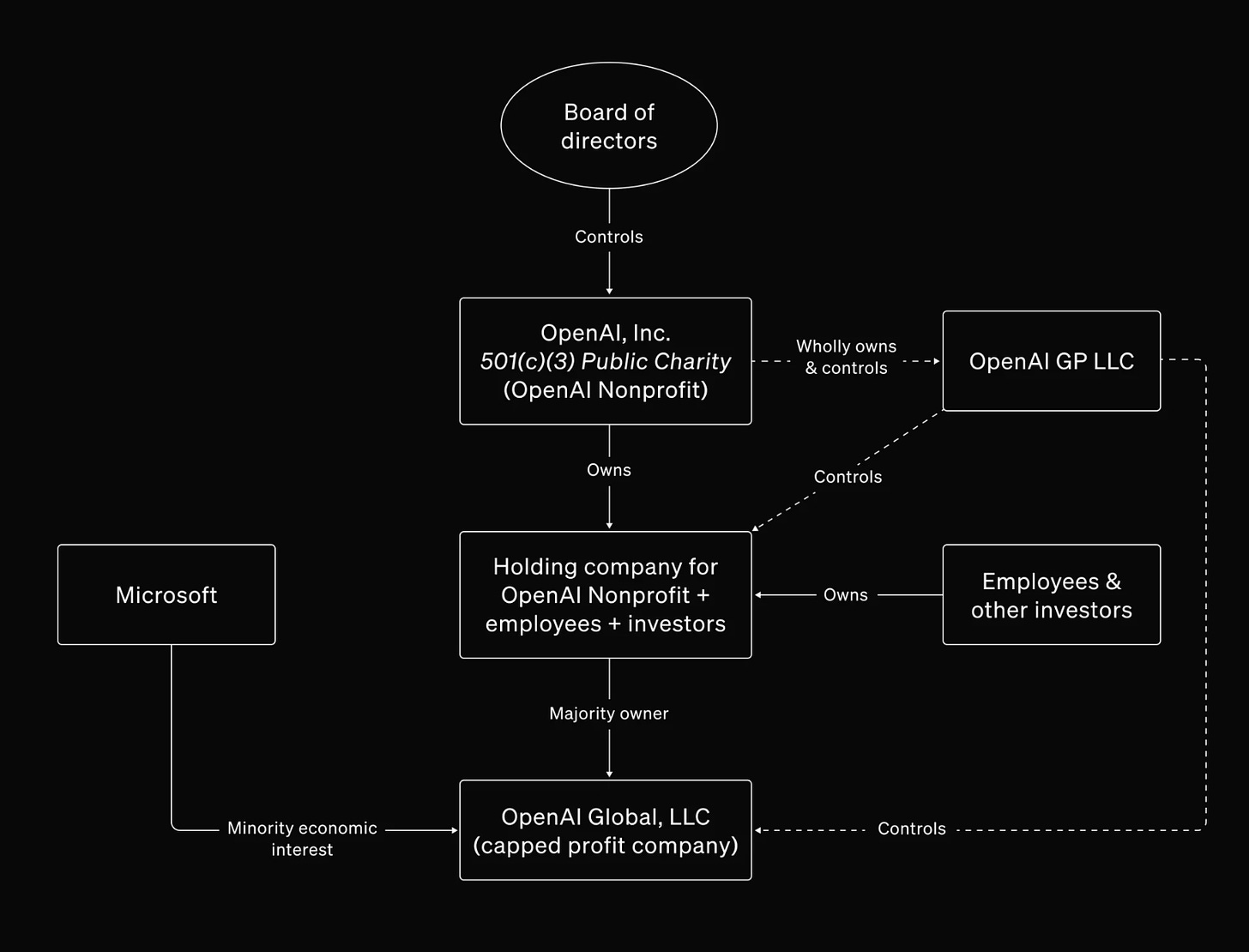

This was a bombshell, but somewhat expected. OpenAI was founded in 2015 as a pure non-profit dedicated to “building safe an beneficial artificial general intelligence2 for the benefit of humanity,” but failed to attract enough donations to be viable, so in 2019, they created a for-profit subsidiary within the non-profit that allowed for capped-profit investments.

Now, they’re planning to dispense with the nonprofit and become a for-profit benefit corporation (B Corp).3 Over time, accusations have bubbled that OpenAI is straying from its original mission and is focusing more on commercializing products (like ChatGPT) over the goal of developing AGI for the good of humanity. But I think that what gets lost in all of this is that at the core of all the 501(c)(3)s and LLCs and org charts is a group of humans that built a company that has rocketed into the stratosphere—latest reports are that OpenAI is targeting a valuation of $150 billion.

What does this remind me of? Bands, specifically ones that have launched into the stratosphere.4 Specifically, the Beatles—with the Beatlemania5 that defined the 1960s, their complicated personal and business relationships, and ultimately their breakup in 1970. Looking back at the Beatles reveals a few key questions that any massive success propelled by a small group of people will have to face. And while it may seem strange or excessive to draw parallels between a group of founders that few people could name with one of the most famous acts ever to exist, regardless of whether the public face of the entity is a company or a band, it’s driven by people, even if the people themselves aren’t on full display (although sometimes they are even in tech: see NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang signing a woman’s chest).

Vision conflicts: What should we do?

Whether a band or a company, a group is always founded with a vision, but sometimes people’s individual interpretations of that vision change. The Beatles were first founded as a skiffle band called The Quarrymen playing live shows in Liverpool. After a few name and personnel changes, they became the Beatles in 1960. When they got down about their prospects, John Lennon would ask, “Where are we going, fellas?” and the others would respond “To the top, Johnny… To the toppermost of the poppermost.” And they made it—in the 1960s, they were the biggest thing in the world, and “Beatlemania” involved screaming crowds, mass hysteria, and the occasional mob or riot. In Florida, it apparently took the band 15 minutes to go 25 feet from an elevator to their car because they only had a dozen police officers on hand, and the only place the group could get some peace was locked in their hotel bathroom. By 1966, George Harrison had gotten sick of Beatlemania, and soon Ringo Starr and Lennon agreed, with only Paul McCartney as the holdout. Eventually he came around, and the Beatles focused on recording until their breakup in 1970.

This was a relatively amicable change in vision. OpenAI’s founding vision was to be a non-profit developing AGI for the good of humanity. The official line that OpenAI “remain[s] focused on building AI that benefits everyone” will never change, but critics question whether OpenAI is abandoning its mission along with its non-profit structure, and having a bunch of high-ranking executives all leave at the same time the structure changes doesn’t exactly help quell those rumors. If that’s the case, then it’s more like a Fleetwood Mac situation, where vision differences allegedly caused a physical altercation between Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks; Buckingham quit the next day. Ilya Sutskever made this pretty explicit when, soon after resigning (he was one of the ones who tried to oust Altman), he founded a new company called Safe Superintelligence.

When a group disagrees about their vision, either consensus has to be reached, or someone has to leave. The Beatles reached consensus and had four more years of creative collaboration ahead of them. OpenAI’s founding group has splintered—it would be like if Ringo Starr joined another band and John Lennon went off and founded yet another. Chaotic? Yes. But also, it probably would have led to some great music—although we never would have gotten Abbey Road.

And if Fleetwood Mac hadn’t been so chaotic, we never would have gotten this live performance of Silver Springs.

Outside pressures are certainly another factor that influence the direction of a company. Management, finances—the Beatles’s media company Apple Corps caused no end of drama—and even fan pressure all impact where a group goes. The Beatles seem to have done a good job of not bowing to external pressure regarding their sound and continued to innovate and experiment with a variety of genres. OpenAI’s accepting of investor money, even with their capped-profit model, has raised concerns that they were no longer able to “remain unencumbered by profit incentives” as their charter states. The new structure tries to balance “commerciality with safety and sustainability, rather than focusing on pure profit-maximization,” but it’s worth questioning how exactly they’re doing this.

Creative differences: How should we do it?

While the vision is about the overall trajectory and goals of a group, the way a group goes about that is governed by their creative approaches. This started to be an issue with the Beatles as each of them developed their own sound. The White Album was famously described as “four solo albums under one roof,” and there were also tensions about some of the members’ burgeoning spirituality and Lennon bringing Yoko Ono into the studio, where there was an unofficial “no wives/girlfriends” rule (although as Maisie Peters sings, “You know Yoko never broke up that band”). Eventually, there was too much tension over who should write what songs and Lennon and Ono’s Plastic Ono Band was well-received, so Lennon decided to leave the Beatles. Then McCartney was planning to release a solo album in close proximity to Let It Be and Starr’s solo album, so they tried to change it, but McCartney reacted badly and quit as well.

When members of a group have strong opinions over how to achieve their vision, there’s inevitably tension. At OpenAI, there have been debates over internal work and management styles, which caused tension that may have contributed to Brockman going on leave. Two issues that have spilled out into the open are open versus closed source and safety testing. Elon Musk sued OpenAI in part because he claimed that they went back on a promise to release all of their code open source, meaning that anyone could build on and use it. This is a questionable argument; OpenAI’s charter reads:

We are committed to providing public goods that help society navigate the path to AGI. Today this includes publishing most of our AI research, but we expect that safety and security concerns will reduce our traditional publishing in the future, while increasing the importance of sharing safety, policy, and standards research.

And, in an email, Sutskever wrote that “The Open in OpenAI means that everyone should benefit from the fruits of AI after its built, but it’s totally OK to not share the science” (to which Musk replied “Yup.”). In 2019, they decided to initially not release all of the source code for GPT-2, before eventually putting it on GitHub. Needless to say, code for GPT-3 and GPT-4 has not been released, and many have criticized the company for it. There are legitimate safety reasons for not releasing all of one’s code, but most are interpreting it as a business decision, and Musk as a betrayal.

WR 37: Monopoly money vs Big Tech politics money

Another thing that some are interpreting as a betrayal is their approach towards safety testing. When OpenAI was trying to launch GPT-4o in time to beat Google’s developer conference, they gave safety teams nine days to complete a comprehensive safety check. The team worked 20 hour days and their metrics indicated that the model was safe enough, but an error they found later showed that it was actually above their threshold for persuasive abilities. Murati was perhaps most impacted by the drive to productize things; she pumped the brakes on several products, but it’s clear that there were differences in opinion on what should be released when. Like the Beatles, individual creative differences—perhaps coupled with disagreements on the overall direction of the company—stressed the structure of the group and contributed to the fracturing of its leadership. Sutskever in particular was head of the Superalignment group, which was disbanded after he left. Unlike with the White Album, there wasn’t room under the same roof for all the different creative visions.

On the subject of day-to-day workflows, there have been questions about whether “legacy” tech companies like Google can compete with OpenAI and other scrappy, new AI startups. With age and size comes bureaucracy, and a corresponding lack of agility (even if they still profess to be "agile"), and there’s speculation that more legacy tech companies may have ossified too much to compete with “move fast and break things” startups—but since this is a question of comparison across companies, we’ll leave it for now.

Personality clashes: How do we get along?

No one can prepare for what it’s like to be launched into the stratosphere. The Beatles were four guys from Liverpool who played at local bars and then suddenly had people threatening to jump off a roof unless they got to meet them. Even if you get along at first, fame and money (and their accompaniments) change people, and I doubt any of the Beatles would have predicted any of their changes in life situation, musical interests, or spirituality. Sometimes that works out well—the Harry Potter kids all stayed friends and stayed sane growing up in the spotlight—but sometimes it ends extremely poorly.

When it comes to tech and OpenAI, you similarly can’t predict when a start-up founded in a garage will suddenly be worth billions of dollars. And this also changes things. As companies grow, you can’t run them like a start-up anymore—you have to have managers, and bureaucracy, and HR.6 There’s also more internal politics, like the “breakdown in communication”—reported to involve a disagreement between Altman and board member Helen Toner about a paper she wrote that criticized OpenAI for publicly launching ChatGPT—that led to the OpenAI board trying to fire Altman.

So, what can we learn from comparing Beatlemania and the rise of OpenAI? I think there’s a few lessons to be drawn, both for OpenAI and for AI companies and start-ups in general.

At the core of every successful venture is a group of people.

With those people come human personalities, conflicts, and foibles, and changes due to fame, fortune, and running something that’s suddenly bigger and more important than anyone ever could have predicted.

If people’s interpretation of the vision changes, they either have to get in line with the dominant interpretation or go.

If there are creative differences, they either have to be housed in a single entity or split off.

Personalities clashes will occur, and how they’re resolved determines the fate of a group.

What does this mean for the future of OpenAI? It’s certainly a different company than it was when it was founded. As a for-profit company, even if its mission is stated the same, its approach will be a lot different and necessarily more focused on commercialization of AI. Utopians will say this will lead to better AI for all of humanity. Doomers will say this will cause unsafe AI releases and maybe even catastrophe. The reality will be somewhere in the middle.

The Beatles held the psyche of nations in their thrall. OpenAI has captured the attention of Silicon Valley, yes, but also governments and techies. And, if they survive the inevitable bursting of the AI bubble, they may hold our technological future in their hands. Let’s hope they’re gentle with it.

Who issued quite a statement about their departures.

Basically AI that can do any cognitive tasks a human can do, but better.

OpenAI competitor Anthropic is a B Corp.

#PrayForChappell

Thanks to Mike for the seed of this idea.

Land of the Giants is a great podcast discussing how Facebook evolved from a college kid startup into the juggernaut of today.