Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. In this Weekly Reckoning, we cover the (possibly) resolved Substack Nazi controversy, the (definitely) under-reported British Library cyberattack and end of an Internet subsidy program in the US, and the (controversially) negotiated SAG-AFTRA deal on using AI in video game voice acting. Then, since I’ve been thinking a lot about the Substack and Boeing boycotts, I work through some thoughts on how boycotts have gotten more complex in our tech-driven, platform-based world.

This edition of the WR is brought to you by: ten inches of fresh powder 🏂

The Reckonnaisance

Substack removes some Nazi publications

Nutshell: In a reversal that they insist isn’t a reversal (but after an intense pressure campaign), Substack is removing five far-right publications.

More: In a statement to Platformer, the biggest publication that threatened to leave the platform, Substack insisted that this is a “reconsidering” of “how it interprets its existing policies,” but they were heavily incentivized to do so by the pressure campaign by publications and subscribers, many of whom may not be satisfied by their fairly weak statement.

Why you should care: Well, again, this is a Substack publication. Substack stated that they’ll be removing five publications (unclear which ones) that it decided violated their rules against inciting violence, but The Atlantic identified dozens of far-right and Nazi publications. Many Platformer commenters said that they were still pausing their subscriptions—which perhaps disproportionately impacts writers, since they receive 90% of subscription fees—but also may continue pressure on writers to switch platforms. Still, it’s unclear how many people have actually left the platform. So… keep watching this space, I guess.

Update 12/1/23: Platformer has announced that they are leaving Substack.

The British Library is slowly recovering from devastating cyberattack

Nutshell: The British Library has been mostly offline since October when it was hit with a ransomware attack, but is slowly restoring its services.

More: The Russia-linked group Rhysida was responsible for the attack and demanded £600,000 to keep them from leaking stolen files. The library refused to pay the ransom, but now will have to spend £6-7 million to rebuild its digital services. And the hackers still profited by selling the library’s data on the dark web.

Why you should care: This has been surprisingly under-reported, perhaps because it’s mostly been impacting academics who rely on it for research (and the librarians, who have been consulting physical logs and running the shelves for months) but shows how national institutions we don’t suspect are vulnerable can be hobbled. It’ll be a year before it can come fully online, and will drain 40% of its reserves to recover. And while the hackers didn’t get a ransom, they still made money, so there’s no incentive to stop.

Shutdown of Internet bill subsidy program set to impact millions of US households

Nutshell: The Affordable Connectivity Program, which subsidized Internet for 23 million low-income households, is winding down this week unless Congress acts to extend it.

More: The US lacks competition and affordability, and doesn’t treat Internet connectivity as a right. During the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, these subsidies helped people a lot, but now WiFi is even more important than before because remote work and school are here to stay, so cutting off families from access is especially cruel.

Why you should care: America can’t seem to figure out how to make broadband affordable, with costs far higher than in the EU and service not necessarily better. Rather than rely on an unreliable Congress to subsidize it for people in need, why can’t we take a leaf out of Europe’s book and treat broadband as a public utility?

SAG-AFTRA reaches controversial agreement on AI voiceovers in video games

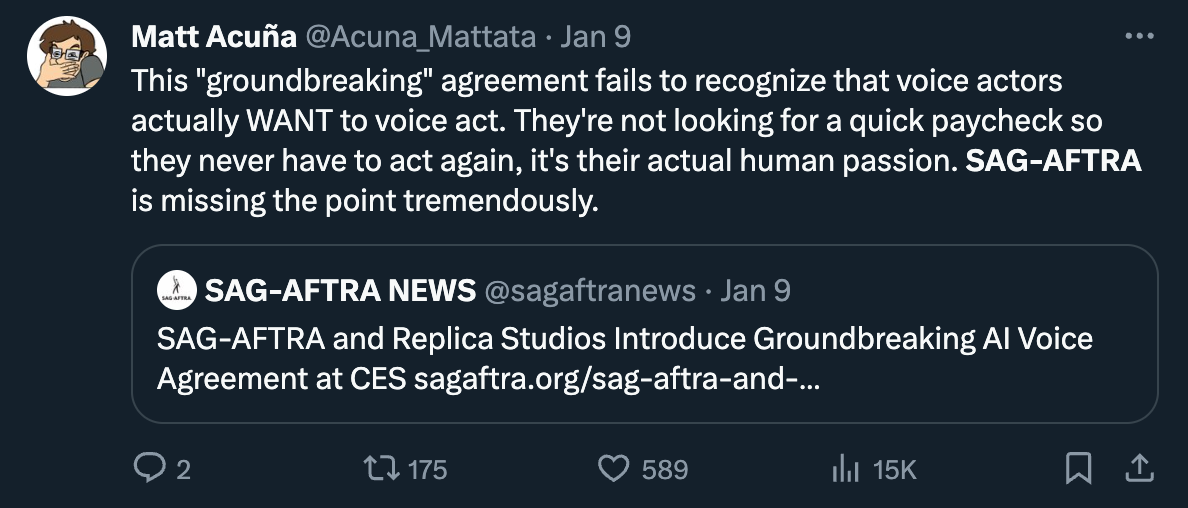

Nutshell: SAG-AFTRA, the performers’ union, inked a deal with AI voice tech company Replica Studio to establish terms for licensing “digital simulations” of voices for video games.

More: Although the union claimed “this is a great example of AI being done right” and that they have “achieved fully informed consent and fair compensation,” many voiceover actors claimed they hadn’t been told about the deal, much less approved it, and that they feel betrayed.

Why you should care: SAG-AFTRA just went through a whole strike about the use of AI, and actors see this deal as a “garbage” betrayal. It’s compounded by the fact that there’s overall less respect for voiceover and video game actors, who are afraid that they won’t be able to work like they have before anymore. My question: what does SAG-AFTRA as an organization gain from this?

Extra Reckoning

Between the Substack conundrum and the Boeing 737 Max scandal, I’ve been thinking about boycotts and what gives us leverage in situations where people can’t directly pressure the parties at fault. I’ve been slightly obsessively following the Boeing 737 Max 9 news: First the panel blow-out, then the revelation that the plane had previous pressurization issues, then reports of “loose bolts” found on other Max 9s and whistleblower reports from the Boeing door supplier… it’s been riveting (if not bolting (I’ll show myself out)). And something seems different then last time the 737 Maxes were grounded. Maybe it’s because I know someone (my aunt) who changed her entire family’s flights because they would not fly on a Max 9—but Twitter is full of people who are also changing their flights because of it. The first Boeing 737 Max crash in 2018 was a tragedy. The second in 2019 was equally tragic, but all the more alarming because it was the second crash. At the same time, one could be excused for thinking that, since they were caused by the same design flaw, Boeing had learned its lesson and shaped up. They fired their CEO and tried to turn over a new leaf. This accident makes it apparent that they haven’t, that production is sloppy and company culture is flawed. Fool me once, shame on me, fool me twice…

I don’t blame people for not wanting to fly on a Max 9. Honestly, not feeling it myself (but thankfully I’m next flying Delta, which doesn’t have any Max 9s). At the same time, once the whopping 4-8 hours of inspection are completed, there’s nothing keeping airlines from putting the planes back into service and countering consumer boycotts by swapping planes at the last minute. The responsibility for the accident ultimately lies with Boeing, who needs to make sure the planes they deliver are safe, but fliers can’t directly target Boeing, and can only imperfectly target the airlines. Thus, the airlines definitely have more leverage over Boeing than consumers, but consumers don’t have much leverage over the airlines. Also, there are really only two companies you can buy huge jets from: Boeing and Airbus. The amounts of money involved (an American Airlines deal for 100 planes under negotiation could be worth $6 billion), time and expense to produce planes, and complexity of the contracts (with commitments to buy specific numbers over specific time frames) means that airlines can’t just throw away their Boeings and stock up on Airbuses. Boeing won’t be hobbled so easily. In this situation, we have low-powered consumers with a moderately-powered middleman facing a high-powered, duopolistic villain, so it’s really on the middlemen to push for change—but if their only incentive is consumers changing their tickets, that won’t be enough. (Bring bad PR into it, though, and we might have more potential leverage…)

The Substack situation is a little different; we saw both individuals and newsletters taking action against Substack for their stance on content moderation, with individuals halting paid subscriptions and newsletters switching platforms. Individual subscribers have more power over middleman publications in this situation, as their contribution is much more significant to a publication than an individual ticket is to an airline and publications don’t really have any recourse—like swapping a plane—if a subscriber chooses to leave. But, only 10% of this money goes to Substack directly, so the individual’s power over the platform is automatically diluted. Thus, it’s again generally up to the middleman publications, who, if they have paid subscriptions enabled, may be more directly swayed by their readers. But most publications are free or earn very little, giving them little leverage over the platform—it’s only because Platformer is a prominent, profitable newsletter and thus has clout that it was able to lead this boycott. So, here we have individuals with little power over the platform but more power over publications, which have somewhere between no and significant sway over the party at fault.

I feel like we’re getting more into the political economy weeds than I’m comfortable with—though I am tempted to draw up a diagram of some sort—because I think the idea of boycotts with middlemen is interesting, especially online. I’m sure there’s a whole academic theory of boycotts out there that I’m not aware of, but the platform-based Internet undoubtedly complicates things. People can directly pressure, say, Twitter to change something, and an organized boycott would directly impact their ad revenues (not that there’s much left of that). Furthermore, leaving the platform doesn’t have as significant collateral damage for creators. No one cares about the harm done to an airline by canceling a ticket—multi-billion-dollar companies don’t need our sympathy—but canceling a subscription to a creator you, on some level, care about takes more thought and thus might hinder organized action against a platform. If Kickstarter did something bad but your friend was funding a project, would you still chip in? Probably. I still have faith that collective action can work, but it seems like in our increasingly complex, tech-driven economy, there are more and more layers we have to account for, and we may be increasingly reliant on the altruistic1 (or appropriately incentivized) actions of middlemen to make change—unless we come up with new forms of organization to encourage them appropriately.

I Reckon…

that if constitutional AI is the next frontier, maybe I should have gone to law school.

Funnily enough, Carrefour is taking a stand against price gouging by dropping PepsiCo products, seemingly without consumer pressure, but obviously with PR benefits.