Welcome back to the Ethical Reckoner. It’s nice to be back after a Labor Day break (yes, I recognize the irony in observing Labor Day by not working). In this Weekly Reckoning, we cover how controversy over AI writing tools is tearing a writing community apart, the foiling of a Russian disinformation plot, steps from YouTube to protect teen mental health, and how US tech investors might bankrupt Honduras. Then, I explore how tech has changed travel through a 1927 book.

This edition of the WR is brought to you by… Superiority Burgers and birthdays

The Reckonnaisance

Writing challenge under fire for promoting AI writing tools

Nutshell: Organizers behind the National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) issued a statement saying that “to categorically condemn AI” in writing is classist and ableist, triggering community backlash.

More: The statement was trying to take a technology-agnostic stance on the use of AI (including things like grammar checkers as well as ChatGPT) but suffered from a failure to distinguish between generative and non-generative AI, as well as a lack of acknowledgement of the very real concerns writers and artists have about generative AI stealing their work, which created the message that writers who don’t support the use of generative AI are classist and ableist. NaNoWriMo walked back the statement to try and nuance it more, but it didn’t stop criticism from all sides, including from disabled writers, who criticized the statement for denigrating their abilities and weaponizing ableism to scare people into agreeing. NaNoWriMo is also sponsored by AI writing companies, raising questions about their motivation and concerns that the challenge is losing its meaning—after all, you wouldn’t hop in a car for miles 2-25 of a marathon.

Why you should care: Most of you will probably never participate in NaNoWriMo nor be directly affected by the inner politics of this organization, but I suspect this is a harbinger of more debates to come—especially since schools and businesses are in the process of figuring out how to deal with AI. One thing they can learn from this debacle is that a careful differentiation between generative and non-generative AI is going to be critical because they have different uses and different ethical questions.

US government takes on Russian disinformation campaigns

Nutshell: The DOJ uncovered propaganda projects, seized 32 Internet domains, and charged two Russians for a scheme to create social media content aimed at swaying the election.

More: The schemes were targeted at sowing discord in the US by seeding fake news stories to decrease public support for Ukraine. Some of the domains seized were fake local news sites (that we discussed in WR 38). The two Russian nationals charged worked for a company linked to RT (formerly Russia Today), a pro-Russia outlet on YouTube and other platforms, and were charged with funneling $10 million to create discordant online content.

WR 38: Enter the AI archeologists

Why you should care: Pretty much everything the DOJ described has nothing to do with AI, showing that good old-fashioned disinformation still exists.1 There’s also an interesting tension here, because Iran has been trying to tip the scales for Harris, while officials believe Russia wants Trump to win, so in a way the US election is the rope in a game of tug-of-war. Regardless, this is actually a heartening story, because this plot is actually getting foiled.

YouTube to limit promotion of videos about weight and fitness to teens

Nutshell: In a new teen mental health move, YouTube will limit “repeat recommendations” of content that idealizes certain physical features, fitness levels, or body weights.

More: YouTube says that this move was developed in consultation with experts on the basis that “teens are more likely than adults to form negative beliefs about themselves when seeing repeated messages about ideal standards in content they consume online” (so basically, when teens see content telling them they should hate their bodies, they start hating their bodies). Intuitive!

Why you should care: Even though this probably could have been done earlier (it may be a response to the UK’s Online Safety Act and other legislation in the EU) but it is a good step that will hopefully help improve the mental health of teens across the world.

US tech investors might bankrupt Honduras

Nutshell: A US company is suing the Honduran government over its attempted elimination of special economic zones for $10.8 billion… 2/3 of Honduras’s annual state budget.

More: Honduras has been trying to rebuild its economy after a military coup and over a decade of corruption. President Xiomara Castro is trying to eliminate “employment and economic development zones” (ZEDEs), special zones that cede “an astonishing level of autonomy” to private corporations, who can establish their own laws, taxes, police, and even courts. They’re unpopular amongst the people of Honduras, both because of how they limit constitutional rights and because of the fear that they’ll “take your land.” Honduras Próspera, a US-based company run by a group of tech investors and venture capitalists that operates the “startup city” ZEDE Próspera, has been targeted and is suing the state for possible lost profits, but this would effectively bankrupt the country. Próspera contains 222 businesses and is known for its experimental medical facilities, which according to the NYT “run clinical trials unburdened by F.D.A. standards” and adjudicated “under the laws of the Próspera ZEDE.”

Why you should care: Honestly, it’s pretty wild to think that a company could bankrupt an entire country, but US companies have done similar things in the past (looking at you, Chiquita). In this case, though, it’s all under the guise of legitimate international law. Still, the mechanism that Honduras Próspera is using is coming under international scrutiny, so that may rally support for the government, but as it stands, Próspera is likely to win their case. They may have the law on their side, but considering there are more than 5400 special economic zones worldwide (some wild successes, like Shenzhen), this may be a cautionary tale for other countries.

Extra Reckoning

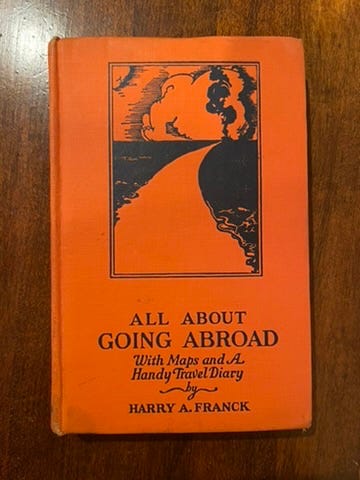

A few weeks ago, I was in a vintage shop in NYC. The clothes were nice, but I got distracted by the carefully curated objects on display, including a battered little orange book called “All About Going Abroad: With Maps and a Handy Travel Diary (by Harry A. Franck). The book was published in 1927, and flipping through it I was enthralled by its discussions of steamships, trains, and trunks (choice quote: “Many a man misses a train which he might easily have taken but for his trunk”) and intrigued by how it hinted at a bygone era where the leisure class could casually gallavant off to Europe for six weeks (you know to schedule an “early interview” with the bath steward and dining room steward, right?).

Unfortunately, the book wasn’t for sale, but $8.89 goes a long way on ThriftBooks, and so now I am the proud owner of a copy. There are loads of fascinating tidbits2 sprinkled throughout (some of my favorites below) but one quote in particular struck me. It was when the book was discussing planes in Europe (transoceanic plane travel wasn’t a thing yet).

Flying saves time; it gives beautiful bird’s-eye views under proper weather conditions; it is an experience to have at least once and be able to tell about at home. But it is one of the poorest ways of ‘doing’ a country in the sense in which the average tourist wishes to “do” it.

This of course got me thinking: what does it mean to “do” a country? Nowadays, it often seems to mean “hit the top spots and take lots of pictures for Instagram.” In other words, the trip is about the destination, not the journey. When this book was written, it was the exact opposite. Traveling anywhere took so long that the trip had to be about the journey: you spent days on a steamer and long stretches on trains, probably stopping in smaller towns en route to the cities (handily enumerated in a list titled “Of First Importance in Foreign Countries”).

Technology has changed travel in a number of ways. Sure, we no longer need to phone in advance to buy hotel coupons or bring traveler’s checks everywhere (and thank heavens for that).

But now we also don’t need to linger on the journey. In my Intro to Science & Technology Studies class, we read Schivelbusch’s “The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century,” which was basically about how the invention of the railroad severed our relationship to physical distance: journeys became about travel time, not the distance you could expect to cover on foot or by horse. It also created a detachment from the landscape, which you saw smearing outside the window rather than all around you. But travel now has not only detached us from the landscape, but from the process of journeying itself. Sure, you still have to sit in a metal tube for a while when traveling overseas. But it’s faster than a train, and much faster than a week on an ocean liner—although boat would make jet lag far easier, as clocks are adjusted by 30-60 minutes at midnight each night.

In a way, though, I think travel served a similar social purpose then as it does now. Sure, the 1927 traveler was seeking out unique experiences and to experience new parts of the world. But they were partially doing this because it’s what was expected of a certian class, and having travel stories to share back home made one seem more interesting and worldly to other members of that class. Now, having travel pictures on Instagram serves a similar signaling function: I’m interesting, I’m cool, I have disposable income. But social media as a medium for sharing lends itself not to the story of the journey; rather, it’s proof of having achieved the destination. You can’t share the details of the sights and sounds and people you met on the train between two countries. You can share a picture of the tourist attractions you saw there.

I’m reminded of when I shared a hostel room in Milan with a group of Instagram influencers. We exchanged a few words but they had their own agenda. When I encountered them at the top of the Duomo doing a full photoshoot, I said hi and they didn’t recognize me.

I don’t think it's a coincidence that some of my friends who have the most interesting travel stories are also the ones who care the least about social media (and are the ones most inclined to travel off the beaten path, often on rugged trails). This isn’t to chastise anyone for their travel choices: I’ve taken many a selfie outside a big European church. But I think it is a reminder to slow down and be less fixated on the destination. Perhaps this is why I love walking in cities so much: it’s how I get a sense of a place’s character. I wouldn’t have found out about the styrofoam lunch bowl economy of Rio if I had subwayed or Ubered everywhere, nor would I have had nearly as many fresh coconut waters. This book is not just a look into how travel was nearly a century ago. It’s also a reminder to enjoy travel for the journey: to embrace the moments when you’re stranded at a Swiss train station, laugh, and buy Biscoff ice cream bars to keep from going insane (a true bonding moment for me and my travel companion); to bask in the light as the forest opens to fields on the border between Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany; to befriend a local and go dance to sertanejo music; to, on a free Sunday, take the train to a random town on the map and explore its markets.

And, most importantly, to never forget your aluminum soap-dish.

“Home again at last, it often happens that your journey in retrospect is the most delightful of all the pleasures of travel, not even expecting anticipation.”

For the curious, here are a few more choice facts from the book:

You could do a four-week journey from NYC through central France for $250 (less impressive when you consider it’s $4500 in today’s dollars, though considering it includes the ocean passage and everything else, still a deal).

An American women married after September 21, 1922, could get a passport on recognition of her own citizenship; a woman married before that had to show proof of her husband’s citizenship, and a non-citizen woman married to an American man after that couldn’t get a passport at all.

12-15 is apparently the correct number of handkerchiefs to bring on a trip.

Champagne and promenading are the recommended cures for seasickness (which is “most likely to visit those who are sure they will be subject to it,” so… mind over matter?).

Americans used to be far better at math, as regarding 24 hour time, the author is confident that the “average American tourist does not find subtracting twelve from figures used between noon and midnight a particularly arduous mental exertion after a little practice”—and more remarkably, that they can divide by 16 and multiply by 25 to convert between kilometers and miles.

“In Japan the so-called sleeping-car is a snare and a delusion, since it consists of little more than permission to lie down on the lengthwise cushions in first or second class coaches.”

“In England it is the ancient custom to tip the servants at a private house in which you have been a guest…Your host will appreciate this last evidence of good taste, since it is a prevailing fiction that he knows nothing about it.”

“The rather general American practice of licking stamps to be affixed to an envelope or licking the flap of envelope is looked down upon among the best circles in many foreign countries. Wet the finger instead, when possible in water.”

“To be without [a walking-stick] is to be mistaken for a man rather than a gentleman.”

I Reckon…

that humans masquerading as robots will never not be funny.

Also a fair bit of casual racism.

Thumbnail generated by DALL-E 3 via ChatGPT with the prompt “Please generate an abstract impressionist brushy painting in shades of orange representing the concept of travel”.

Thank you so much for the post about AI and NaNoWriMo. I didn't know about their AI statement--and just reading about it made me angry. I am an author/writer who spends months painstakingly writing and editing my novels. And before I became an author, I would spend days or weeks working on/crafting/editing magazine articles. So when I hear about able-bodied/minded people using AI, which steals the work of others, to create something they claim to have written themselves, it infuriates me. (Note: As you point out in your post, spell- and grammar checkers--or using dictation (speech to text) as part of the writing process--are not the same thing as using AI to create an article or book, and I have no problem with those particular tools.)